Manufacturing Update - 6 May 2025

Insights from articles and reports of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad

Content:

1. A SECOND CHINA SHOCK? “Trump is Paving the Way for another ‘China Shock’” (Interview with economist David Autor)

2. AUTO TARIFFS WILL STILL HIT US CARMAKERS HARD: “Automakers could still face up to $12,000 impact per car from tariffs”

3. MANUFACTURING SECTOR CONTRACTING: “Manufacturing activity hits 5-month low as Trump tariffs leave businesses in 'state of near paralysis'”

4. TARIFFS UNDERMINE US AUTOMAKERS’ FUTURE IN ELECTRIFICATION AND AUTONOMY: “Trucks and Tariffs are a Disastrous Combination for Big Auto”

5. UKRAINE’S INNOVATIVE DRONES: “Building and leveraging Ukraine's drone

capabilities in conflict & beyond: Assessing the defense/security innovation ecosystem”

6. US INFOTECH EXPORTS WILL BE HARD HIT BY TARIFFS: “Retaliatory Tariffs Could Cut US ITA Exports by $56 Billion”

7. CHINA WANTS A POWERHOUSE BIOTECH SECTOR –WHAT ARE THE CHALLENGES? “A Biotech Sector Toolkit”

1. A SECOND CHINA SHOCK?

“Trump is Paving the Way for another ‘China Shock,’” (Interview with economist David Autor) Roge´ Karma, Atlantic, April 29, 2025.

Intro: To the extent that Donald Trump’s trade war with China is based on a coherent story about the world, it is this: Free trade with China has been a disaster for the American worker, and we need tariffs to reverse the damage.

No one knows more about that story than the MIT economist David Autor. In 2016, he co-wrote a paper with David Dorn and Gordon H. Hanson that challenged the economics profession’s rapturous view of free trade. Drawing on their previous research, Autor and his co-authors concluded that from 1999 to 2011, the rise in Chinese imports had cost roughly 2 million American workers their jobs, with the bulk of those losses coming in the years immediately following China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001. In the subset of factory towns where the damage was most concentrated, entire communities fell into ruin. The authors called the phenomenon “the China shock.”

The same year that the paper came out, Trump ascended to the White House—in part by railing against free-trade agreements and promising to bring back jobs from overseas. Later research found that he had overperformed in counties that had been hardest hit by trade with China, helping him win key swing states such as Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania. The phrase China shock was suddenly being spoken all over Washington. And in the coming years, a new bipartisan consensus emerged that restricting trade with China was necessary to protect American workers.

Broadly speaking, Autor shares that view. His research findings have convinced him that the old free-trade consensus was wrong. But he also believes that Trump—who has imposed sweeping 145 percent tariffs on nearly all Chinese imports, and who seems to announce or walk back some new trade policy at least once a week—is challenging that consensus in the most counterproductive way possible. In Autor’s view, Trump’s tariffs will actually weaken American manufacturing, with the potential for damage far greater than what the country experienced the first time around. “I think the Trump folks are asking the right question,” he told me. “But they’ve come up with just about the worst answer.”

Comments by Autor: The “China Shock” paper came out of the fact that China started exporting a rising number of manufactured goods to the U.S. in the 1990s and early 2000s. Most economic models envision a scenario where labor markets adjust to changes like this pretty smoothly. The effects are broad and diffuse. Most people displaced find employment opportunities in other sectors. There might be an effect on earnings, but it is pretty small.

What we found instead was a really large effect on employment rates in the labor markets that were most exposed. In aggregate, we estimate that about 1 million to 1 million and a half manufacturing workers were directly displaced. If you consider spillovers to other sectors of the economy, it’s about 2 million workers. In these areas, we also saw a decline in earnings, an increase in child poverty, an increased dependence on programs like Medicaid and disability insurance. And these places didn’t recover quickly, if at all.

If this had happened over the course of 20, 30 years, it wouldn’t have done so much damage. People would have had time to adapt. There would have been a lot of natural attrition and turnover to smooth things out. But most of the China shock happened over just seven years. That’s what made it so painful.

I think the Trump folks are asking the right question. But they’ve come up with just about the worst answer. It’s a classic case of fighting the last war. They’re looking over their shoulder, wishing we hadn’t made the mistakes we made 20 years ago. But what they are doing now is just compounding the errors.

The jobs that we lost to China 20 years ago: We’re not getting those back. China doesn’t even want those jobs anymore. They are losing them to Vietnam, and they aren’t upset about it. They don’t want to be making commodity furniture and tube socks. They want to make semiconductors and electric vehicles and airplanes and robots and drones. They want those frontier sectors.

As it happens, those are the sectors we’ve actually held on to. But we could lose those too. We could lose Boeing. We could lose GM and Ford. We could lose Apple. We could lose the AI sector. These are the parts of manufacturing that generate good jobs but also so much more than that. They are where innovation occurs, where the big profits are, where technology and military leadership come from. And those are the sectors that we stand to lose next.

So the goal shouldn’t be to reverse the first China shock. It should be to prevent a China shock 2.0.

But these tariffs are going to do the opposite. We’re not just putting tariffs on tennis sneakers. We’re putting tariffs on steel, on rare earths, on machine parts, which means we’re raising the cost of the inputs for all the things we make. That makes those frontier sectors way less competitive. If we want to keep these industries flourishing, we need them to be able to export to the rest of the world. And who the hell is going to buy our cars or planes if we’ve suddenly made them more expensive?

We can learn something from China’s example. Ten years ago, China decided they wanted to be at the frontier of a handful of sectors: drones, semiconductors, EVs, solar cells, etc. And for those sectors, they did a combination of protection alongside a lot of public investment. There was also some intellectual-property theft in there, for sure. But the bottom line is, China is now a leader in many of those sectors. Companies like BYD or Xiaomi or Huawei are some of the best in the world. They don’t even need the protection or the subsidies anymore. They are just good.

You also may need to protect these sectors with policies like tariffs. But that’s a targeted set of protections, sort of like the tariffs the Biden administration put on things like EVs and solar cells and semiconductors from China last year. And you need to combine that with huge government investments, commitments to public purchasing, investments in universities, bringing skilled talent from overseas, expanding the H-1B program. There’s lots and lots of things you can do.

But it’s important to remember that China has 120 million manufacturing workers; we have 13 million. We’re not going to be able to achieve their kind of scale on our own. So we need to pick and choose our battles, and then we need to work with our allies in that project.

Just look at the whiplash the auto companies are experiencing. They made all these investments in EVs, and now we’re saying we’re going to go back to clean coal and internal-combustion engines? This is crazy. These companies have made huge, costly investments. Even though Tesla is tanking, consumer demand for EVs is rising. And we’re all of a sudden going to say, “No, turn your back on that.” That’s a death wish. Fifteen years from now, almost no one will be driving an internal-combustion car. They’re just not as good.

Letting free trade rip is an easy policy. Putting up giant tariffs is an easy policy. Figuring out some middle path is hard. Deciding what sectors to invest in and protect is hard. Doing the work to build new industries is hard. But this is how great nations lead.

And right now, the United States is giving up on all of those things, even as China is doubling down on them. As a very patriotic person, I find that absolutely heartbreaking. We can do better.

Excerpted with edits; more at (paywall): https://www.theatlantic.com/economy/archive/2025/04/trump-china-shock-manufacturing/682631/

2. AUTO TARIFFS WILL STILL HIT US CARMAKERS HARD

“Automakers could still face up to $12,000 impact per car from tariffs,” David Shepardson, Reuters, May 1, 2025

A Michigan-based economic consulting group said on Thursday that automakers will still face a $2,000 to $12,000 tariff impact per vehicle despite the White House moving to soften trade levies on imported auto parts. Anderson Economic Group said U.S. assembled vehicles like Honda's Civic and Odyssey, the Chevy Malibu, Toyota Camry, and Ford Explorer faced an impact of $2,000 to $3,000. But that could rise to as much as $10,000 to $12,000 for imported vehicles, including full-size luxury SUVs, some EVs and other vehicles assembled in Europe and Asia, such as the Mercedes G-Wagon, Land Rover and Range Rover models, some BMW models, and the Ford Mach-E

The Ford Explorer assembled in Chicago previously faced a tariff impact of about $4,300, which will drop to about $2,400, the group estimated, while some Jeep, Ram and Chrysler models from Stellantis could face a $4,000 to $8,000 hit.

GM said on Thursday that it expected a hit from tariffs of up to $5 billion, including $2 billion on vehicles it imports from South Korea.

Earlier this week, Trump agreed to give carmakers two years to boost the percentage of domestic components in vehicles assembled in the United States. It will allow them to offset tariffs for imported auto parts equal to 3.75% of the total value of the Manufacturer’s Suggested Retail Price of vehicles they build in the U.S. through April 2026, and 2.5% of U.S. production through April 2027.

Auto industry leaders lobbied the administration furiously during the weeks since Trump first unveiled his 25% tariffs on imported vehicles and auto parts. The levies, aimed at forcing automakers to reshore manufacturing domestically, had threatened to upend a North American automotive production network integrated across the U.S., Canada and Mexico. The White House said the change will not affect the 25% tariffs imposed last month on the 8 million vehicles the United States imports annually.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/automakers-could-still-face-2000-12000-vehicle-price-impacts-tariffs-2025-05-01/

3. MANUFACTURING SECTOR CONTRACTING

“Manufacturing activity hits 5-month low as Trump tariffs leave businesses in 'state of near paralysis,’” Josh Shafer, Yahoo Finance, May 1, 2025

US manufacturing activity slid to a five-month low in April as President Trump’s tariffs continued to create uncertainty for businesses.

The Institute for Supply Management’s manufacturing PMI fell to 48.7 in April, below the 49 seen the month prior. Readings below 50 indicate contraction in the sector. The ISM's prices paid index for the sector came in at 69.8, roughly flat compared to the prior month. Meanwhile, new orders increased to a reading of 47.2, above the 45.2 seen in March.

"In April, U.S. manufacturing activity slipped marginally further into contraction after expanding only marginally in February," Institute for Supply Management chair Timothy Fiore said in a press release. "Demand and output weakened while input strengthened further, conditions that are not considered positive for economic growth." The ISM release includes comments from survey respondents across various industries.

Economist Thomas Simons (from Jefferies US, an investment banking firm) wrote in a note to clients on May 1 that nearly all of the comments "described a state of near paralysis" as businesses struggle to account for the changing tariff policies. "The tone of these comments suggests that business planning is impossible for the majority of manufacturers, irrespective of their industry specialty," Simons wrote. "Frankly, it is a surprise that the index levels are as high as they are. These comments are consistent with a PMI reading in the 20s or 30s."

In a separate release on Thursday, S&P Global's manufacturing data showed activity held flat at a reading of 50.2 in April. Meanwhile, S&P Global noted that tariff impacts boosted both input and selling costs. "It tells me that this process that started with the policy uncertainty and then moved to the markets is now starting to show up in the real data," S&P Global Ratings global chief economist Paul Gruenwald said. "That's kind of the last leg of this transmission." Gruenwald added that the "key variable" for the economy moving forward will be whether or not the labor market deteriorates further.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/manufacturing-activity-hits-5-month-low-as-trump-tariffs-leave-businesses-in-state-of-near-paralysis-152727991.html

4. TARIFFS UNDERMINE US AUTOMAKERS’ FUTURE IN ELECTRIFICATION AND AUTONOMY

“Trucks and Tariffs are a Disastrous Combination for Big Auto,” Liam Demming, Bloomberg Opinion, April 29, 2025

When BYD Co. Ltd. announced its newest electric vehicles could recharge in just five minutes, it represented a big problem for Tesla Inc. Rival CATL then unveiled an even-faster-charging battery - this is a big problem for US automakers in general. Here is a game-changing technology being defined by two Chinese powerhouses while the US, spiritual home of autos for much of the past century, merely looks on.

America’s auto industry faces three simultaneous disruptions. First, even as EVs struggle to grow their share of the US market, they continue to take market share from internal combustion engines globally. Second, advanced driver-assistance systems, or ADAS, and other IT increasingly define the design, experience and value of vehicles. Third, China has emerged as a leader in both. President Donald Trump’s rhetoric about the US wresting back leadership of global autos is rooted in these real challenges. His actions, though, threaten to consign Detroit to outright irrelevance.

China makes and buys more EVs than the rest of the world combined. This year, it should become the first major market where sales of cars with a socket overtake those without. China dominates the battery supply chain, not just in quantity but, as the charging wars show, cost and innovation, too.

EVs still cost an average of $12,000 more than their gas-guzzler peers in the US. The cheapest, the Nissan Leaf, starts at just under $30,000. Chinese drivers can pick from an array of EVs below that level, including BYD’s sub-$10,000 Seagull mini-compact car. For many years, Detroit, like its European, Japanese and Korean counterparts, profited from China, gaining access via joint ventures that seeded domestic competitors. The latter are now devouring their local market and exporting millions of vehicles. US companies’ vehicle sales in China are forecast to collapse 75% by 2030 compared with the start of the decade to under a million units, according to Alix Partners, a consultancy.

While the US spawned the company that brought EVs into the mainstream, Tesla, its leader Elon Musk seems more interested in politics these days — and a brand of politics unfriendly to EVs. Musk has also readily admitted that Chinese car companies are the most competitive in the world, and Tesla’s market share in China has come under sustained pressure. BYD, having retaken the top spot in global battery EV sales last quarter, just announced earnings that trounced Tesla’s.

In terms of driver assistance and the drive for autonomy, the picture is more nuanced. The US and China are the only countries in the world with commercial robotaxis operating today. Advanced testing of self-driving passenger vehicles, however, is more widespread. All the major auto manufacturers worldwide offer some type of ADAS, such as Tesla’s Autopilot and Full Self Driving or Mercedes-Benz Group AG’s Drive Pilot.

The fusion of digital smarts with vehicles is at once an opportunity and a threat. The only commercial robotaxi firm operating in the US is Waymo LLC, a unit of Alphabet Inc. Forays into autonomy by Detroit have stalled. GM’s recent decision to ditch its in-house robotaxi effort, Cruise, owed something to scandal but also to a simple acknowledgement that GM doesn’t have Alphabet’s balance sheet. A subsequent partnership with Nvidia Corp. to provide, among other things, hardware and software for smarter cars is a sensible alternative. But, as with Waymo’s Silicon Valley roots, it raises the nagging question of who will end up reaping the lion’s share of the value from the next generation of vehicles, Big Auto or Big Tech?

Tesla is different, with an in-house approach that has always had more of Silicon Valley’s DNA embedded in it; plus, of course, that giant market cap. Rather, its dilemma is that, despite repeated pledges of unleashing millions of genuinely self-driving EVs, it has yet to deliver an actual commercial product.

Here, too, China complicates things even if tariffs keep its cars out of the US market. In February, BYD said its God’s Eye ADAS product would be offered on most of its models, including those ultra-cheap EVs, as standard. For Tesla, which charges Chinese drivers more than $8,000 for its Full Self Driving feature, this adds pressure in a competitive market where it is already giving away profits through incentives. Moreover, two-thirds of American ADAS industry executives say that Chinese technology already meets US technical requirements, according to a recent poll by Alix Partners.

Europe’s auto giants face similar challenges, but it has put less stringent tariffs on Chinese autos than the US has. Brussels is also exploring other options including allowing Chinese auto companies entry to Europe on the proviso that they form joint ventures with local companies or license their technology, effectively running Beijing’s earlier playbook in reverse. This risks ceding market share, of course; after all, it took China’s homegrown companies many years to outpace their foreign partners.

Without that, though, tariffs alone will likely dull the edge of competition that results in things such as ultra-fast charging at lower prices. Nowhere is this risk more acute than in the US, where Tesla is losing its luster and Detroit is already overly dependent on big SUVs and trucks that have little relevance elsewhere. Yet rather than helping the sector navigate this epochal challenge, Trump’s administration offers a mix of moving tariffs, threats to tear up their North American supply chains and an ideological attachment to tailpipes. Protectionism can buy time, of course — but using that time well requires coherent industrial policy. Absent that, the US auto sector risks becoming ever more like an island of (expensive) misfit toys amid a sea of markets ceded to Chinese manufacturers

Excerpted with edits; source at (paywall): https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2025-04-29/trucks-and-tariffs-are-a-disastrous-combination-for-big-auto

5. UKRAINE’S INNOVATIVE DRONES

“Building and leveraging Ukraine's drone capabilities in conflict & beyond: Assessing the defense/security innovation ecosystem,” Darna Ostrafichuk, Phil Budden and Fiona Murray, MIT Management/Kviv School of Economics, March 1, 2025.

If necessity is the mother of invention, then war is the mother of Ukraine's defense and security innovation ecosystem. As with other origin stories of innovation ecosystems in times of conflict including e.g. the Greater Boston ecosystem which to a large extent was forged in the Rad Lab at MIT during World War II, or Silicon Valley’s early origins in the radio communications needs of the Pacific fleet in the post-World War I era, it is only by analyzing the extent of stakeholder engagement that we can learn lessons for the future.

From this initial research, we have several key insights:

Ukraine’s wartime innovation in the production and use of drones (especially UAVs in the air domain) has rightly captured international attention, but learning the right lessons for others requires some close analysis about how that happened.

Prior to February 2022, like many other nations, Ukraine’s post-Soviet ‘military-industrial complex’ had not appreciated the nature of war changing, even though development of many drones had started after the 2014 invasion, with the Russian occupation of Crimea and the war in the ‘Donbas’ region.

Since the full-scale Russian invasion in February 2022, however, a Ukrainian ‘whole of nation’ response underpinned the rise of a multi-stakeholder innovation ecosystem which we refer to as a defense/security innovation ecosystem (DSIE), with an emphasis on the development, production and delivery of drones of increasing scale and sophistication.

From close study of this period, it is clear that a key source of the success of this innovation ecosystem involved a network of individuals and organizations drawing from all five stakeholder categories – start-up entrepreneurs, risk capital, government and (but to a lesser extent) large corporations and universities.

Domestic actors in each stakeholder category were supported - to a greater or lesser degree and in different ways - by foreign stakeholders from a range of countries. In addition to a few nations’ special forces, there was also support through informal networks of preexisting relationships or through the agency of individuals as much as formal government to government activities.

Especially interesting for those learning from Ukraine is that it took a nation moving to a wartime footing to mobilize the full range of mostly non-state actors to achieve the progress that has been observed, and that few state systems - even those with an effective military industrial complex, and with effective government and corporate actors - have delivered such comparable innovation.

With February 2025 marking the third anniversary of the Russian invasion, now is a moment to reflect with Ukraine and its Allies, and to inform options for:

Ukraine to continue to capitalize on its hard-won, conflict-driven defense/security innovation ecosystem.

Ukraine to ensure its security through sustainable production of the drones it needs (with productive uses of its additional manufacturing capability ‘surplus’).

Ukraine to benefit more broadly from the prosperity that can arise from its tech breakthroughs including from the scale of its domestic production that may allow for export opportunities.

These considerations, if well developed and implemented, should provide Ukraine with

more resilient paths to prosperity in a post-conflict (even if not fully peaceful) future, linking its defense and security innovation ecosystem and wider civilian ecosystems to those across Europe, and integrating with the rest of Europe to build a more prosperous future.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://murray-lab.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/UkraineDroneEcosystem-Analysis_2025.pdf

6. US INFOTECH EXPORTS WILL BE HARD HIT BY TARIFFS

“Retaliatory Tariffs Could Cut US ITA Exports by $56 Billion,” Rodrigo Balbontin, ITIF, April 23, 2025

Bringing manufacturing back to the United States is the right goal for the Trump administration, but slapping indiscriminate tariffs on the world undermines that very mission. Countries will retaliate, hampering U.S. tech exporters, undermining U.S. competitiveness, and handing American firms’ hard-earned global market share to foreign rivals.

Once the market uncertainty from the initial tariff announcements fades, these measures will likely lead to some expansion of domestic production and an increase in U.S. foreign direct investment. However, the additional negative effects will likely undercut these objectives. American manufacturers that sell in global markets may reduce their U.S. exports due to the rise in input costs—and that does not account for foreign retaliatory tariffs. Foreign retaliation will reduce U.S. exports of many advanced goods. (ITIF modeled the impact of retaliatory tariffs on goods covered under the World Trade Organization’s Information Technology Agreement (ITA).)

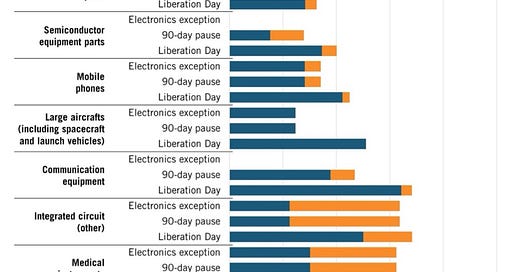

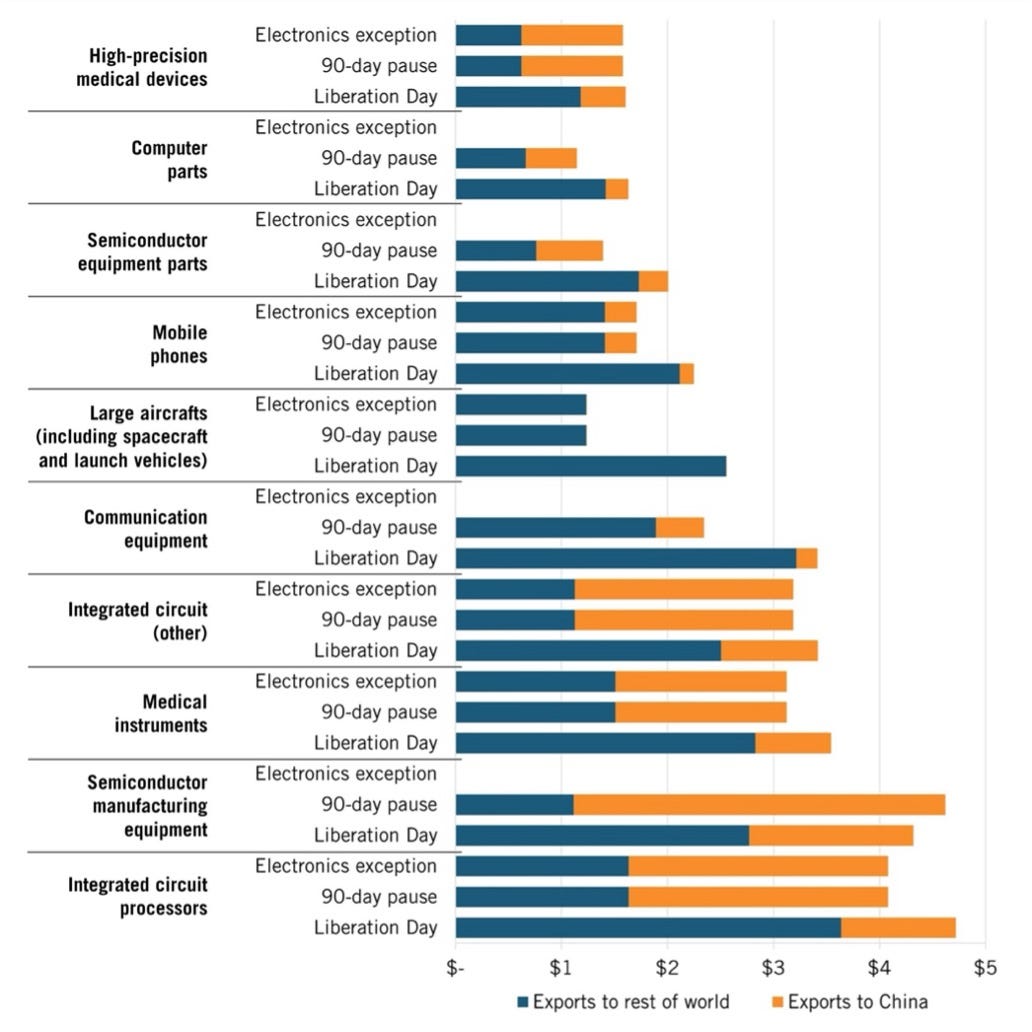

ITIF calculated three scenarios of tit-for-tat retaliation: “Liberation Day” tariffs, the 90-day pauseof reciprocal tariffs announced a week later, and the exemption on 20 products announced a few days after that. We found that U.S. exports of goods covered under ITA would decline due to retaliation by $82 billion, $70 billion, or $56 billion, respectively. These losses represent 18 to 27 percent of total U.S. exports of ITA products, shrinking American technology firms competing in global markets, where they would likely lose more global sales than their foreign competitors. ITIF’s calculation also utilizes 2023 import data from the Atlas of Economic Complexity.

Table: Potential losses of American exports of ITA products ($ billions)

Per ITIF’s model, the top 10 products most affected products in the “Liberation Day” retaliation scenario, presented in in the chart below, account for 36 percent of the total estimated loss in exports. Some of these products could not be affected by retaliation, as they are part of the 20-product exemption, such as those related to semiconductor manufacturing equipment. However, exports of high-tech products such as integrated circuits and satellites (included in “other large aircrafts”) will face a reduced demand from retaliation regardless of the circumstances. Even without counting China, blanket tariffs would reduce ITA (Information Tech Agreement) exports by $28 billion.

Chart – US exports in 10 affected ITA advanced tech areas that could be affected by retaliatory tariffs ($ billions):

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://itif.org/publications/2025/04/23/retaliatory-tariffs-could-cut-us-ita-exports-by-usd56-billion/

7. CHINA WANTS A POWERHOUSE BIOTECH SECTOR –WHAT ARE CHALLENGES?

“A Biotech Sector Toolkit,” Angela Shen, China Talk, May 1, 2025.

(The story summarizes a report by the National Security Commission on Emerging Biotechnology:https://www.biotech.senate.gov/finalreport/chapters/?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email). The global biotech market is now truly massive:

Investment levels: China has identified biotechnology as a strategic priority. Budget allocations reflect this shift: China spent roughly US$34 billion (RMB 249.7 billion) on science and technology in 2024, and earmarked US$55 billion (RMB 398.12 billion) for 2025. However, disaggregating biotech from broader S&T initiatives — and parsing where spending falls across research, development, and commercialization — remains difficult. For instance, China’s 2024 investment of US$4.17 billion in bio-industrials and biomanufacturing is hard to categorize by stage. What’s clear is that the bulk of China’s biotech policy continues to prioritize biopharma, the most dominant part of the sector.

System efficiency: The efficiency of China’s public biotech funding ecosystem also requires investigation. One Chinese professor observed: “Money is no longer a major issue… the problem is with the funding system.” Government ministries, national foundations, and provincial and municipal governments all deploy biotech-linked funds, and a lack of coordination and transparency between actors can lead to redundant or wasteful effort. Fund allocation is also uneven, often favoring large, top-down projects aligned with national priorities — an approach that can be ill-suited to biotech, where breakthrough directions are inherently unpredictable. High competition and the short-term structure of grants further limit incentives for more high-risk innovation.

Private capital is equally important to understand. In key application areas like pharmaceuticals and agriculture, private investment plays an outsized role in shaping what gets developed and what reaches the market. China was the second-largest destination globally for biopharma venture funding in 2018–2019, raising around US$60 billion. Such a metric is less impressive in comparative terms: the US raised US$212 billion in the same period, and China’s innovative capabilities remain limited by its less robust private sector. But since the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s capital markets have cooled, and many biotech firms have scaled back R&D. The survival rate and long-term viability of these Chinese start-ups remain undecided.

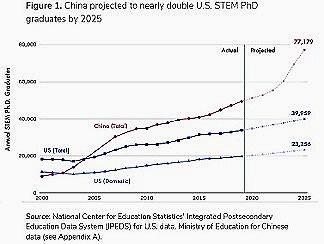

What is the size of China’s talent base, and how sticky is it? Over the past two decades, China has modernized its education system with the goalof cultivating world-class science and technology talent. Government education expenditure as a share of GDP rose from 2.5% in 1998 to over 4%since 2012 and has stayed above this benchmark through 2024. Such investment spans all levels of education: primary and secondary schools are integratingmore STEM into their curriculums, and the number of STEM undergraduateand PhD degrees awarded in China grows each year.45% of China’s STEM PhDs now come from top “double-first-class” universities, indicating their quality

However, academic programs may still fall short when it comes to preparing talent for biotechnology. In one survey, a third of Chinese biopharma companies reported R&D development issues, citing academic curricula that lag behind industry needs. Industry experience, including the ability to translate research into commercial products and to build and lead globally competitive biotech firms, remains underdeveloped. This gap in managerial and translational expertise has become a core constraint on ecosystem growth. While China’s high-skilled STEM workforce is expanding, it still represents a relatively small share of the overall population. The imbalance between supply and demand has led to intense competition for talent — reflected in an 18% active turnover rate in pharmaceutical R&D in 2020.

Beijing is also seeking to bring back Chinese professionals educated or employed overseas. The National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars supports scientists conducting basic research, provided they spend at least nine months a year in China. The Thousand Talents Plan offers returnees signing bonuses, high salaries and funding, housing assistance, and family support. Such programs, while not unique to China, intend to strengthen the country’s domestic research and innovation capacity.

These programs have mixed effects. Government statistics report a growing number of returnees each year. At the same time, both the flow of Chinese students going abroad and the rate at which they stay overseas after graduating have held steady. As of 2019, for instance, over 90% of Chinese AI talent educated in the US has chosen to remain in the US. While China has become more attractive for returnees — thanks to rising living standards, a growing private sector, and increased R&D investment — many of the original push factors remain. Concerns about academic and political freedom, limited job prospects, and digital censorship continue to shape decisions to stay abroad. Some of those who do return are face lower than expected salaries, shortages of postdoc positions and jobs, and reverse culture shock.

Demographic pressures are pushing China to diversify its talent base. China’s college-aged population is decliningand has been on a marked downward trend for more than a decade. Ongoing labor market challenges are likely to further drive down Chinese postgraduate enrollment. Beijing has made efforts to attract global talent, including a series of immigration reforms in 2017, but those reforms have yielded limited results. Since 2017, China has risen only modestlyin the Global Talent Competitiveness Indexand still ranks below the top 35 countries. Fewer than 7% of the country’s PhD enrollments are foreign. Political, professional, linguistic, and cultural barriers continue to limit China’s appeal to global researchers.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://www.chinatalk.media/p/how-to-build-biotech-strategy

Since 2022, MIT has formed a vision for Manufacturing@MIT—a new, campus-wide manufacturing initiative directed by Professors Suzanne Berger and A. John Hart that convenes industry, government, and non-profit stakeholders with the MIT community to accelerate the transformation of manufacturing for innovation, growth, equity, and sustainability. Manufacturing@MIT is organized around four Grand Challenges:

1. Scaling advanced manufacturing technologies

2. Training the manufacturing workforce

3. Establishing resilient supply chains

4. Enabling environmental sustainability and circularity

MIT’s Bill Bonvillian and David Adler edit this Update. We encourage readers to send articles that you think will be of interest to us at mfg-at-mit@mit.edu.