Manufacturing Update - 6 February 2025

Insights from articles and reports of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad

Table of contents for article summaries below:

Tariffs and coping with China’s overproduction: the “Second China Shock” and the role of tariffs

Trump tariffs and the North American production system: Trump protectionism – the salvos at Mexico and Canada

EVs are now a major industrial sector – will emissions regulations continue to drive EV acceptance? - The EV fight moves to California

Biden administration wraps up Chips Act R&D spending awards

Biden administration completes $6b Rivian EV financing deal

New manufacturing facilities for military AI: AI military start-up Anduril plans $1 billion factory in Ohio

DoD and SBA set up investment funds for scale-up financing for critical technologies

1. TARIFFS AND COPING WITH CHINA’S OVERPRODUCTION

“The Second China Shock and the Pettis Paradigm – Will Tariffs Help Rebalance the World Economy?” Noah Smith, Noahpinion, Jan. 16, 2024

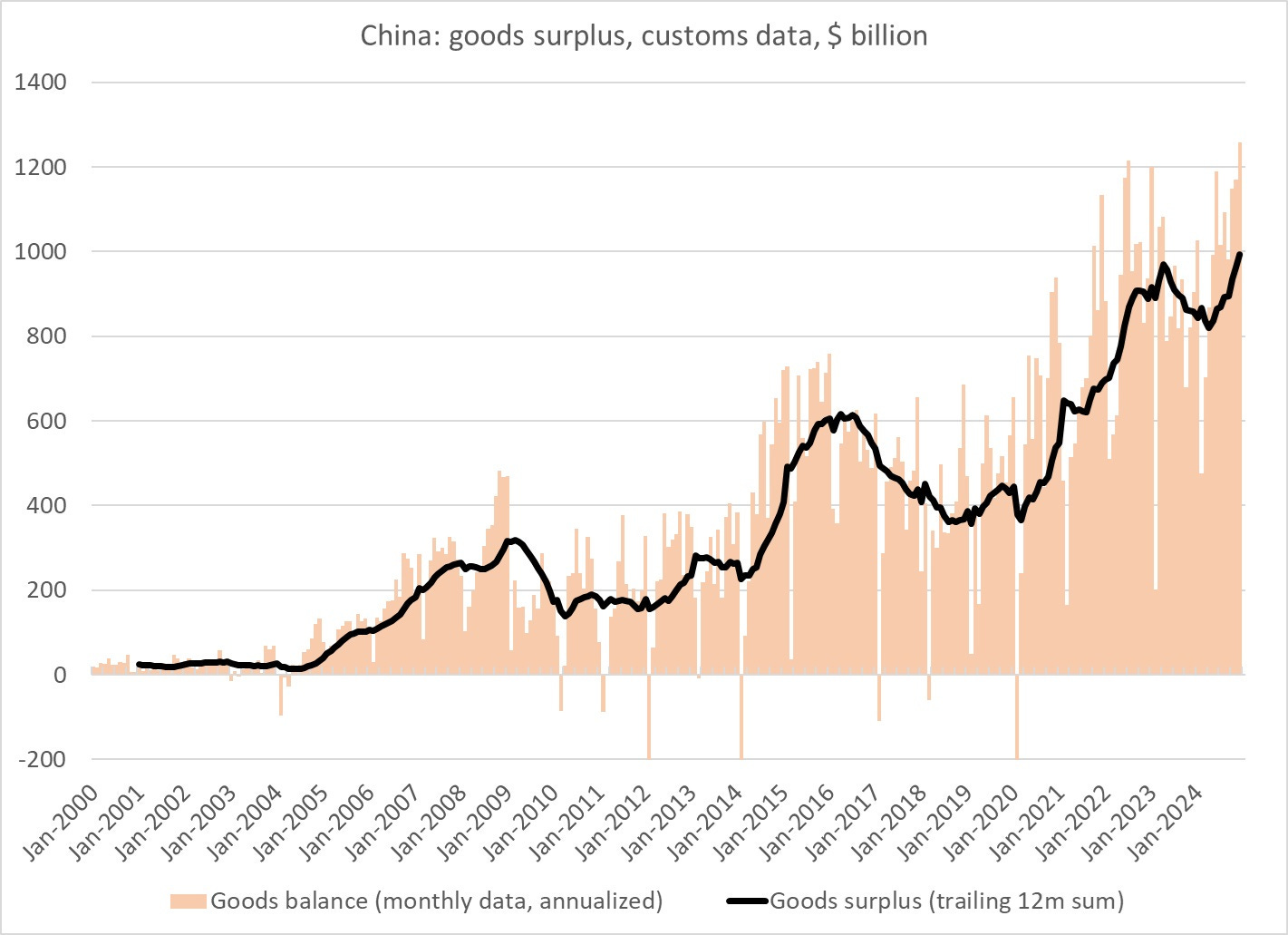

China has a huge and growing trade surplus, as you can see in the chart above. Interestingly, China’s exports to the developing world are a much bigger factor here than its exports to the U.S. and the EU, though the latter [already massive] are up by a bit. This is the Second China Shock. Trade surpluses like this can’t be explained by the good old theory of comparative advantage — a Chinese trade surplus is just countries writing China IOUs in exchange for physical goods. Countries don’t really have a comparative advantage in writing IOUs.

Why trade surpluses and deficits do happen is an important and interesting and complex question. It probably has something to do with the fact that China’s government is directing its banks to loan vast amounts of money to manufacturers, and paying manufacturers tons of subsidies on top of that. But there also has to be some sort of financial factor involved that prevents China’s currency from appreciating and allowing Chinese people to buy more imports.

The question is what to do about the vast flood of Chinese exports. Overwhelmingly, from all sides of the commentariat, there has been one main policy proposal for the world outside of China: tariffs on Chinese goods. The MAGA people, obviously, endorse this idea. In addition, some commentators suggest that China should shift its economic model toward promoting domestic consumption instead of yet more manufacturing. Many commentators who don’t explicitly endorse tariffs will nevertheless say that if China doesn’t shift toward consuming more of what it produces, the world inevitably will put tariffs on Chinese goods.

The “other countries should put tariffs on China” idea and the “China should shift its economy toward domestic consumption” idea are unified in the worldview of Michael Pettis, who has advocated both things. Pettis is now probably the single most influential economics theorist today.

Pettis has stated that, “Today, [unlike in the 1930s], Americans consume far too large a share of what they produce, and so they must import the difference from abroad. In this case, tariffs (properly implemented) would have the opposite effect of [the] Smoot- Hawley [tariffs of the 1930s]. By taxing consumption to subsidize production, modern-day tariffs would redirect a portion of U.S. demand toward increasing the total amount of goods and services produced at home. That would lead U.S. GDP to rise, resulting in higher employment, higher wages, and less debt. American households would be able to consume more, even as consumption as a share of GDP declined…Thanks to its relatively open trade account and even more open capital account, the American economy more or less automatically absorbs excess production from trade partners who have implemented beggar-my-neighbor policies. It is the global consumer of last resort. The purpose of tariffs for the United States should be to cancel this role, so that American producers would no longer have to adjust their production according to the needs of foreign producers. For that reason, such tariffs should be simple, transparent, and widely applied (perhaps excluding trade partners that commit to balancing trade domestically). The aim would not be to protect specific manufacturing sectors or national champions, but to counter the United States' pro-consumption and anti-production orientation.”

So far, China’s main methods of fighting its real-estate-induced recession is to pump up manufacturing production, especially in capital-intensive high-tech industries — machinery, ships, planes, cars, batteries, drones, semiconductors, and so on. Xi is making the Chinese economy look a little bit more like the old Soviet one, where production was determined by plans instead of by the market. He’s using banks and industrial policy to tell Chinese companies to build a bunch of specific high-tech manufactured products, and they’re doing what he’s telling them to.

Why did this approach fail in the USSR? Ultimately, it was because Soviet manufacturers were inefficient — they made a bunch of stuff, but they produced it at a loss. That was unsustainable. Chinese factories are a lot better than Soviet ones were. But if you tell enough different manufacturers to all produce the same stuff at the same time, they’re going to compete with each other, and their profits will mostly fall, and they’ll start taking big losses.

In fact, we can already see this starting to happen in China:

Exporting your way out of a recession is fine and good — it’s basically how Germany and South Korea shrugged off the Great Recession in the early 2010s. But China’s export boom is heavily subsidized, both with explicit government subsidies, and — more importantly — with ultra-cheap abundant bank loans. Subsidies are distortionary — they mean that China is making the cars that Germany and Thailand and Indonesia and other countries would be making for themselves if markets were allowed to operate freely. By subsidizing exports on such a massive scale, China is distorting the whole global economy. So why should we care if China wants to dump low-cost goods on us?

Well, three reasons.

First, if a wave of underpriced Chinese exports forcibly deindustrializes the rest of the world — a possibility I’m sure Xi Jinping has considered — then it could weaken the world’s ability to resist the military power of China and of Chinese proxies like Russia and North Korea. That’s scary.

Second, even if a bunch of cheap Chinese stuff looks like a gift in the short term, it can create financial imbalances that cause bubbles and crashes in other countries. This is the “savings glut” hypothesis for why the global economy crashed after the First China Shock in the 2000s.

And third, a flood of cheap Chinese stuff can cause disruptions and chaos in other economies, hurting lots of workers a lot even as it helps most consumers a little.

Michael Pettis also argues that cheap Chinese stuff actually makes Americans poorer, by reducing their domestic production so much that Americans actually end up consuming less. So what should countries do to prevent this? Tariffs are one obvious answer. If the world raises tariffs on China high enough, exchange rates will have difficulty adjusting, and Chinese products will have difficulty penetrating foreign markets. Chinese companies will then have to fall back on their domestic market. This will intensify the effect of competition and reduce their profits much more quickly.

The sooner Chinese companies’ profits collapse, they will cut back on production. They’ll also probably pressure the government to stop subsidizing overproduction, to lessen the competitive effect and keep themselves in the black. This political pressure could be what finally pushes Xi Jinping and the CCP to change China’s economic model, reducing incentives for overproduction.

Matthew C. Klein, who co-authored the book Trade Wars are Class Wars with Pettis, and who recently wrote an op-ed explaining how tariffs could easily backfire. He writes: “Spending on manufacturing imports tends to track the business cycle and new orders for American-made goods. Imposing “universal” tariffs high enough to force those imports to fall by more than 40 percent to close the trade deficit would likely involve a severe economic downturn that hurts Americans more than anyone else. To avoid that pain, domestic production of those same goods would have to rise enough to cover the gap — and rise fast enough to prevent shortages and inflation. The experience of the pandemic suggests that this is not a realistic option ….

Another counterintuitive impact is that the dollar tends to become more expensive in response to the imposition — or threat — of new tariffs …. [This] means that goods made in the U.S. become more expensive for customers in the rest of the world. The net effect is that tariffs often hit exports more than imports, even when foreign trade partners fail to retaliate.”

Pettis doesn’t really seem to grapple with the point. It’s possible that he believes that Trump’s first-term tariffs were a failure because China simply rerouted its exports through Vietnam; in this case, putting tariffs on all other countries, as Pettis recommends, would close off that loophole. But that still wouldn’t deal with the question of exchange rate appreciation. Unless tariffs on the rest of the world are so huge that they overwhelm the dollar’s ability to adjust to compensate, some sort of financial intervention to keep the dollar weak would be necessary in order to make tariffs effective. Pettis has suggested taxing capital inflows, which could do the trick, but this kind of intervention doesn’t seem on the table for the Trump administration.

And Pettis also fails to grapple with the intermediate goods problem. The U.S. would not benefit from going back to the kind of quasi-autarkic economy it was during World War 2 — technology has changed too much for any country to prosper while walling itself off from the rest of the world. The U.S. can onshore and harden its supply chains to some extent, but no matter what, U.S. manufacturers are still going to have to order some materials, parts, and components overseas. I haven’t yet seen Pettis suggest a solution to this problem or think hard about the failure of Trump’s tariffs to increase industrial production in the U.S. six years ago. While Pettis’ paradigm probably does a good job grappling with the unique characteristics of the Second China Shock and China’s political economy, I don’t think we should rush to make it our general default paradigm for thinking about trade, tariffs, and international economics in general.

Excerpted with edits; more at (paywall):

2. TRUMP TARIFFS AND THE NORTH AMERICAN PRODUCTION SYSTEM

“Trump the Protectionist: Canada and Mexico are the First Salvos,” Rob Atkinson, ITIF, February 2, 2025

President Trump is and always has been a protectionist. So, in assessing his rationale for slapping across-the-board tariffs on Canada and Mexico, forget the notion that they have not enforced their borders and have thus allowed fentanyl and illegal immigrants to flow into the United States. That’s just a smokescreen. (Consider that Canada has more opioid deaths per-capita than the United States.) He simply needed the pretext of an emergency so he could invoke the U.S. International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) and impose tariffs to benefit U.S. companies, his true end game.

What is behind Trump’s radically nationalistic protectionism? First, he is reacting to the excesses of the globalists who dictated trade policy in Washington from the 1980s to 2016. If they had their way, there would be no tariffs and little trade enforcement, even against China. But while it is true that the pro-globalization establishment had become too rigid and attached to the outdated idea of an international economic utopia with no borders to trade, Trump and his apostles are proving themselves to be what could be called “antipodalists”—people who habitually take things to the absolute opposite extreme. If the last phase of global trade was bad, then by their logic the only fix is to close our borders, to everything. Don’t even bother with how to make globalization work for America in a new and complicated world in which China has emerged as America’s existential threat.

Second, Trump embraces protectionism because he was always a national businessman, and his circle included other national businessmen, running companies that largely sold to U.S. consumers. Many of these companies find a home in the Coalition for Prosperous America (CPA), a lobby group representing domestic producers. At least CPA is clear about its goal: “to advocate [for] the implementation of strategic trade, tax and growth policies so our members can prosper.” There is nothing wrong with an interest group lobbying for its members’ interests. What is wrong is when they incorrectly claim that their members’ interests equal the national interest.

Finally, Trump is a protectionist because, in his heart, he wants to return the Republican Party to its pre-New Deal ways. From Lincoln to Hoover, the Republican Party was the party of tariffs, because its power base was the industrialized Northeast and Midwest, where industries benefited from high tariffs that shielded American industry from foreign competition. William McKinley, the strongest advocate for high tariffs, is often called the “Napoleon of Protection.” Like McKinley, Trump—who calls himself “Tariff Man”—sees tariffs as the principal economic development tool.

Unfortunately, the initial responses to Trump’s tariffs have been predictable, but impotent. Some rightly say that it will raise prices. Well, so what? That’s the point: Given America’s massive trade deficit, it needs to raise prices of imports by devaluing the dollar and restricting unfairly made Chinese imports. The issue is not price increases, per se, but whether they are warranted to achieve an overarching goal. Others argue that it will lead to a trade war. Well, of course it will. Trump doesn’t care; he’s Tariff Man and his arsenal is far bigger than Canada’s and Mexico’s combined. Others claim Trump’s actions violate global principles of free trade. You might as well waive a red flag in front of a bull with that argument. The Trumpian protectionists wear that as a badge of honor.

Instead, there are three main arguments opponents need to make.

This beef with Canada and Mexico is trivial. America’s real adversary is China, which is an unreconstructed mercantilist, which is now engaged in a campaign of advanced industry predation designed to take over the commanding heights of global advanced industry production. If that happens, China becomes the global hegemon and America a drawer of water and a hewer of wood, without companies and industries that need global markets to succeed.

Without allies, America will lose the war against China. Full stop. Trump’s trade aggression will only alienate the United States from its allies, and it may encourage them to side with China, especially as you can bet Xi Jinping will play the “America is a protectionist, China follows the rules” card for all it’s worth. Trumpian isolation is a path to American decline. It’s the exact opposite of making America great again.

A key way to beat China is to develop a North American production system. The global free traders wrongly thought there’s no appreciable difference between producing potato chips and producing computer chips, and ironically Trumpian protectionists are making the same mistake. The former group didn’t care whether America had either industry onshore; they assumed the U.S. economy could simply import them. Whereas, the latter crowd wants both onshore, as if they’re equally valuable. Moreover, Trumpian protectionists believe there should be no division of labor, even within North America. The United States should make everything it consumes, even low-skill products that Mexico can make. This is not just economic nonsense, but also a prescription for GDP decline. As bad as the past phase of globalization may have been, correcting course shouldn’t involve rejecting the basic notion of comparative advantage. The United States will never be able to onshore low-wage production (unless it levies massive tariffs), nor should it want to. The goal for U.S. policy should be to encourage low-wage production to leave China for Mexico and other parts of Latin America, while integrating with Canada even more.

What is most troubling about Trump’s actions is that they show he is abandoning national developmentalism—the economic doctrine that prioritizes advanced-industry dynamism and selective globalization—which is the best way to ensure that the West stays technologically ahead of China. In Trump’s mind, China and Canada are both guilty of the same sin of running a trade surplus with America. Ergo, America has been a “sucker” in its dealings with both of them. Never mind that Canada’s tariffs on the United States are lower than U.S. tariffs on Canada, and with the exception of a few non-critical industries, like milk and wood, Canada generally plays by the rules. And never mind that Canada’s trade surplus with America would disappear tomorrow if Trump stopped defending the value of the U.S. dollar.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://itif.org/publications/2025/02/02/trump-the-protectionist-canada-and-mexico-are-the-first-salvos/

3. EVs ARE NOW A MAJOR INDUSTRIAL SECTOR – WILL EMISSION REGULATIONS CONTINUE TO DRIVE THEIR ACCEPTANCE?

“The Electric Vehicle Fight Turns to California: The future of EVs might hinge on a decades-old air pollution law; Whether the law is upheld will have ramifications far beyond the borders of the Golden State,” Aarian Marshall, Wired, Jan. 28, 2025

California loves its electric cars. More than 2.1 million battery-powered vehicles are driving around the state, and last fall, over a quarter of new cars sold there were electric. Lawmakers are trying to ensure the future holds even more. In December, California received special permission from the US government to enact regulations that would require automakers to sell only zero-emission new vehicles in the state by 2035.

The permission, in the form of a federal “waiver,” should extend well beyond California’s borders. Seventeen other states have said they would follow California’s lead on stricter emissions standards, with 11 targeting the 2035 gas car phase-out. Together, these states account for more than 40 percent of US new light-duty vehicle registrations.

Or maybe not. Last week, in a wide-ranging executive order targeting green energy policies, the Trump administration said it would seek to “terminate” state emissions waivers “that function to limit sales of gasoline-powered automobiles.” The order, at this point more political messaging document than anything with the force of law, puts California’s clean car goals in the Trump administration’s crosshairs. Whoever wins this fight could determine the future of electric vehicles not just in the US, but—given the number of vehicles both sold and made in the country—globally, too.

The Trump administration has not yet officially moved to revoke the waiver, but California says it will not back away from its more stringent vehicle emissions standards. “California will continue to defend its longstanding right and obligation to protect the health of its residents,” Liane Randolph, the chair of California’s emissions regulating agency, the Air Resources Board, wrote in a statement.

California’s waiver dates back to 1967, when congressional lawmakers decided to create a special California exemption within national air regulations because the state had such a thorny air pollution problem, and because it had been a pioneer in regulation, creating its own vehicle emissions regulations for more than a decade. Since then, California has applied for more than 100 waivers. In 2019, President Donald Trump announced by tweet that his administration would revoke the California waiver allowing it to set its own auto emissions standards.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://www.wired.com/story/the-electric-vehicle-fight-turns-to-california/

4. BIDEN ADMINISTRATION WRAPS UP CHIPS ACT R&D SPENDING

“Commerce Completes Site Selection for Major CHIPS R&D Facilities,” Clare Zhang, AIP FYI, Jan. 9, 2025

On Jan. 6, the Commerce Department announced that the National Semiconductor Technology Center’s (NSTC) Advanced Packaging Piloting Facility will be sited at the Arizona State University Research Park in Tempe, Arizona. The Commerce Department has now selected sites for all three flagship R&D facilities within the NSTC, the multi-billion-dollar initiative funded by the CHIPS and Science Act to foster domestic semiconductor innovation. The packaging facility aims to ease the scaling of new chips to full production by uniting activities “across the full technology stack for semiconductors,” from prototyping to packaging, in a single facility, according to the department’s facilities plan. It will be fully operational in 2028. The sites for the other two flagship facilities were announced in the fall.

The other two facilities are: 1) The Design and Collaboration Facility in Sunnyvale, California will conduct research in chip design, electronic design automation, chip and system architecture, and hardware security. It will also house NSTC administrative functions and serve as the headquarters for the Workforce Center of Excellence. It is expected to become operational this year. 2) The Extreme Ultraviolet Accelerator in Albany, New York will focus on advancing the state of the art of the highest resolution lithography tools essential for manufacturing leading-edge microchips. It will provide access to some EUV technology this year, and more advanced tools in 2026.

Summarized with edits; more at: https://ww2.aip.org/fyi/commerce-selects-sites-for-chips-r-d-facilities

5. BIDEN ADMINISTRATION COMPLETES UP $6B RIVIAN EV DEAL

US Finalizing Billions for Rivian, Plug Power Before Trump Retakes Office, Ari Nater, Bloomberg, Jan. 16, 2025

The Department of Energy announced Thursday the closing of $6.6 billion in financing for Rivian to construct a Georgia manufacturing plant. It also confirmed Latham, New York-based Plug Power will get a $1.66 billion loan guarantee for hydrogen plants. The financing comes as the Energy Department’s loan program — which effectively became a $400 billion green bank during Joe Biden’s presidency — faces new threats from Trump’s incoming administration.

Rivian, in a statement, said its financing would accelerate expansion of the company’s new R2 SUV and R3 crossover, and was “key to U.S. leadership in the electric vehicle industry.” Plug said its funding would be used for the construction of as many as six projects, the first to benefit being its Graham, Texas, green hydrogen plant.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/us-finalize-billions-funding-rivian-021727249.html

6. NEW MANUFACTURING FACILITIES FOR MILITARY AI

“A.I. Military Start-Up Anduril Plans $1 Billion Factory in Ohio - The company said its Columbus plant could eventually produce tens of thousands of autonomous systems and weapons each year,” Cade Metz and Eric Lipton, New York Times, Jan. 16, 2025

Anduril, a technology start-up that designs autonomous systems and weapons for government agencies and the military, plans to build a $1 billion factory in Columbus, Ohio, the company said on Thursday. It said the factory, called Arsenal-1 and described as a “hyperscale” plant, would bring more than 4,000 jobs to Ohio and eventually produce tens of thousands of autonomous systems and weapons each year.

“We will be creating with our partners in Ohio something that does not currently exist” at such a scale, Anduril’s chief strategy officer said in a briefing with reporters. The company has worked closely with state officials on the project and has secured tax breaks to locate it in Columbus. Anduril, based in Costa Mesa, Calif., is among a new wave of defense start-ups working to build autonomous systems and weapons for the military using the latest artificial intelligence technologies. They include flying drones, underwater vessels and surveillance towers that could be deployed along national borders or on a battlefield.

Excerpted with edits; more at (paywall): https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/16/technology/anduril-factory-columbus-ohio.html

7. DOD AND SBA SET UP FUNDS FOR SCALE-UP FINANCING FOR CRITICAL TECHNOLOGIES

“Department of Defense and U.S. Small Business Administration Publish Names of First 18 Licensed and Green Light Approved Funds for the Small Business Investment Company Critical Technologies Initiative,” DOD Release, Jan. 16, 2025

The Department of Defense (DoD) has selected the first cohort of “Licensed and Green Light Approved” investment funds under the Small Business Investment Company Critical Technologies Initiative (SBICCT Initiative). The Initiative is a partnership between the DoD and the Small Business Administration to strengthen U.S. national and economic security by attracting and scaling private investment into the DoD Critical Technology Areas (CTAs) and into component-level technologies and production processes.

Collectively, this first cohort is projected to invest over $4 billion in over 1700 portfolio companies focused on all 14 CTAs and on strategic component technologies and production processes. These investment funds hail from all regions of the country with offices in 15 states. After receiving the "Green Light Letter," each fund is invited to raise private capital. When the fund is ready to close on the initial tranche of private capital, that fund will apply to receive its SBIC license – after which it will be able to access its approved leverage and begin investing in portfolio companies. Seven funds in the first cohort are fully licensed and have commenced investment activity.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://www.defense.gov/News/Releases/Release/Article/4032999/department-of-defense-and-us-small-business-administration-publish-names-of-fir/

Since 2022, MIT has formed a vision for Manufacturing@MIT—a new, campus-wide manufacturing initiative directed by Professors Suzanne Berger and A. John Hart that convenes industry, government, and non-profit stakeholders with the MIT community to accelerate the transformation of manufacturing for innovation, growth, equity, and sustainability. Manufacturing@MIT is organized around four Grand Challenges:

1. Scaling advanced manufacturing technologies

2. Training the manufacturing workforce

3. Establishing resilient supply chains

4. Enabling environmental sustainability and circularity

MIT’s Bill Bonvillian and David Adler edit this Update. We encourage readers to send articles that you think will be of interest to us at mfg-at-mit@mit.edu.