Manufacturing Update - 30 December 2025

Insights from articles and reports, excerpted and summarized, of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad.

Content:

CHINA SHOCK DÉJÀ VU: “China Shock 2.0 is Coming for Your Advanced Manufacturing”

OVERALL: We’re at year’s end, and the single most important US and world manufacturing development of 2025 arguably was China reaching a manufacturing trade surplus of $1 trillion despite US tariffs. This issue is allocated to a single provocative article analyzing this issue, which includes extensive tables and charts.

1. CHINA SHOCK DÉJÀ VU: “China Shock 2.0 is Coming for Your Advanced Manufacturing,” Michael Kovrig, Strategic Narratives, December 8, 2025

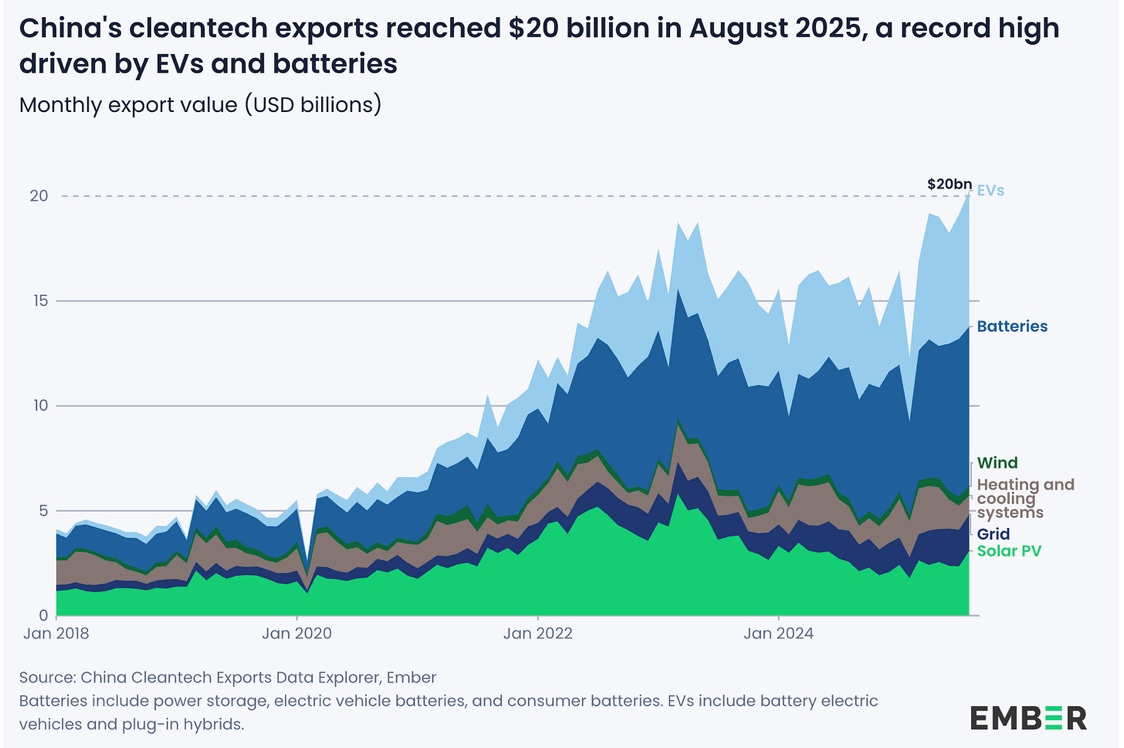

Over the past year, analysts and economists have begun warning of a Second China Shock in which China’s manufacturing overproduction is unleashing a torrent of subsidized exports that’s already further deindustrializing advanced economies and risks preventing emerging markets from fostering infant industries.

China Shock 1.0 hollowed out a lot of basic manufacturing in advanced economies. Now China Shock 2.0 is coming for high tech industries. Grappling with economic weakness at home, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is determined to further turbocharge industrial competitiveness and exports in its relentless drive for regime security through national greatness and global primacy—even at the cost of destabilizing the world economy and breaking down the rules-based trading order.

This tectonic shift in trade has huge geoeconomic, geopolitical and geostrategic implications which I’ve been tracking for years but haven’t had time to write much about publicly. As the evidence begins to mount, here’s a quick-and-dirty compilation of key points to kick off a discussion on this monster topic.

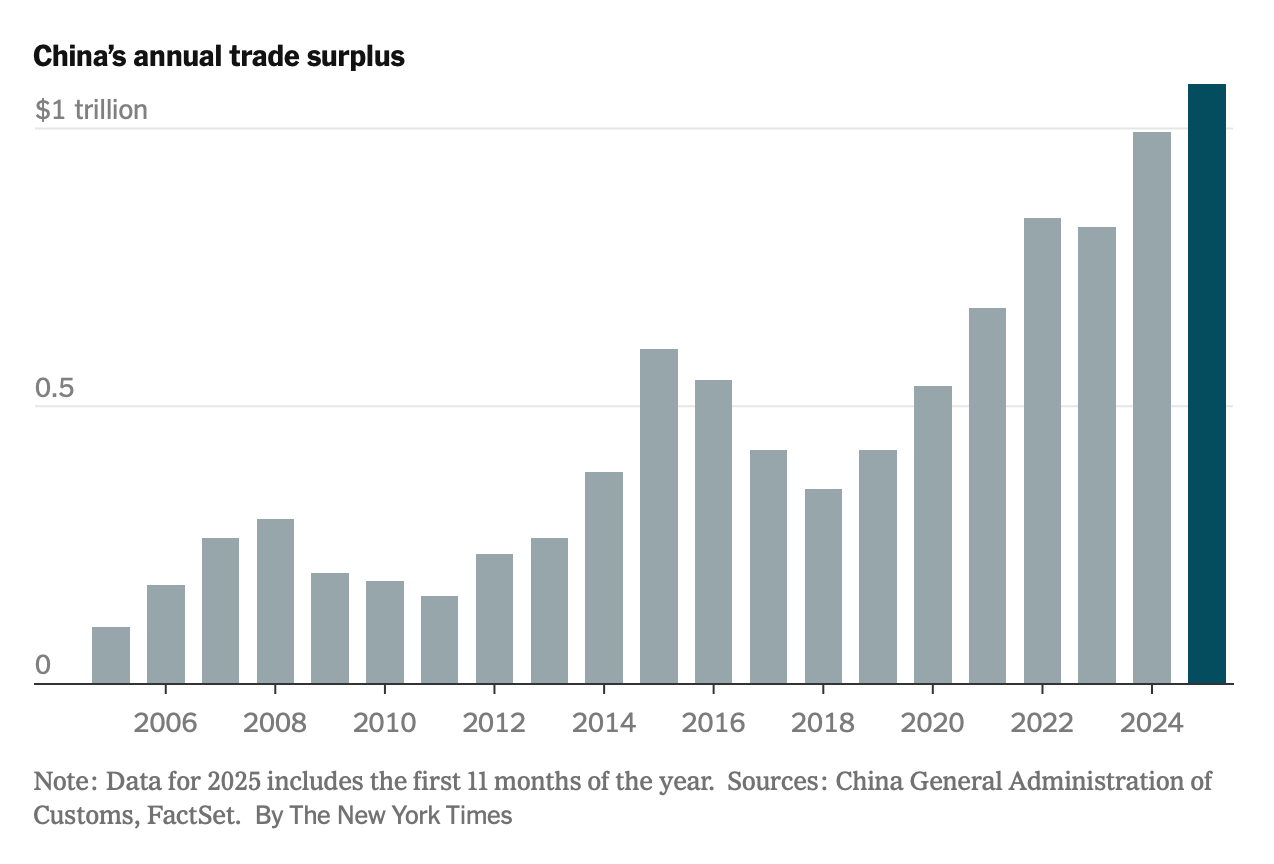

China’s Trillion Dollar Trade Surplus

The latest data indicate China’s accumulated trade surplus (exports minus imports) has kept growing, reaching a new peak of $1.08 trillion by the end of November—higher than the annual total for 2024, and up over 21% year on year, as the New York Times reports. “Strip out imports of energy, food and raw materials, and China is on track this year to post a surplus in manufactured goods of around $2 trillion,” the Wall Street Journal notes. That’s equivalent to the GDP of Russia, and twice the level in 2020.

Source: “China’s Trade Surplus Climbs Past $1 Trillion for First Time”, New York Times

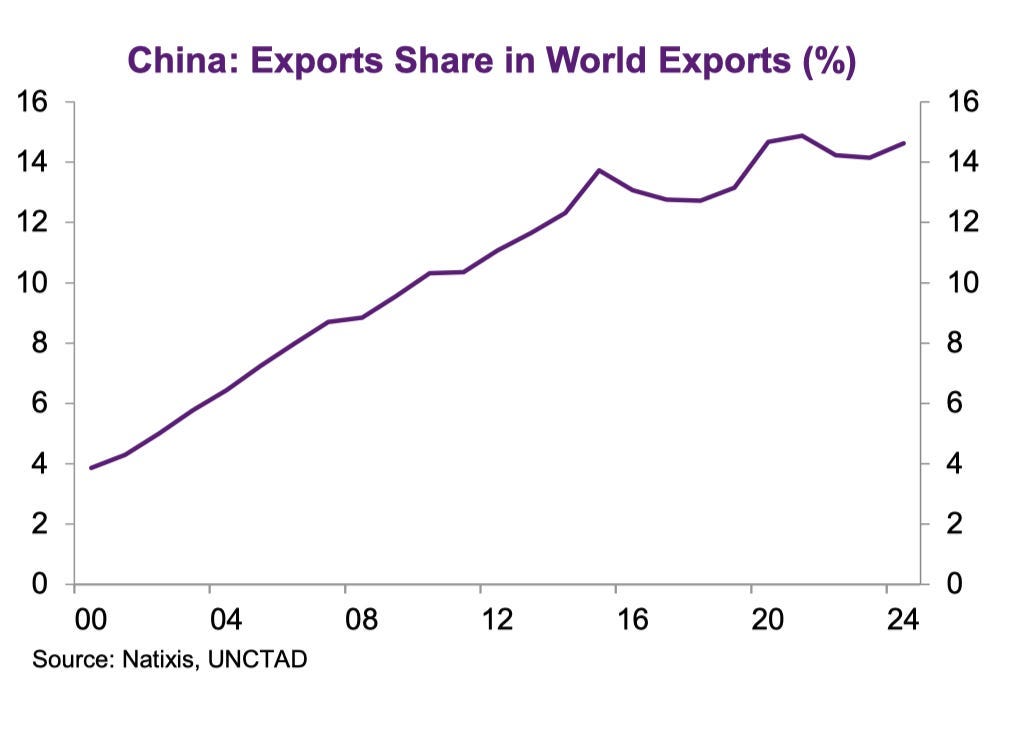

In recent years, China’s exports have grown three times faster than global trade.

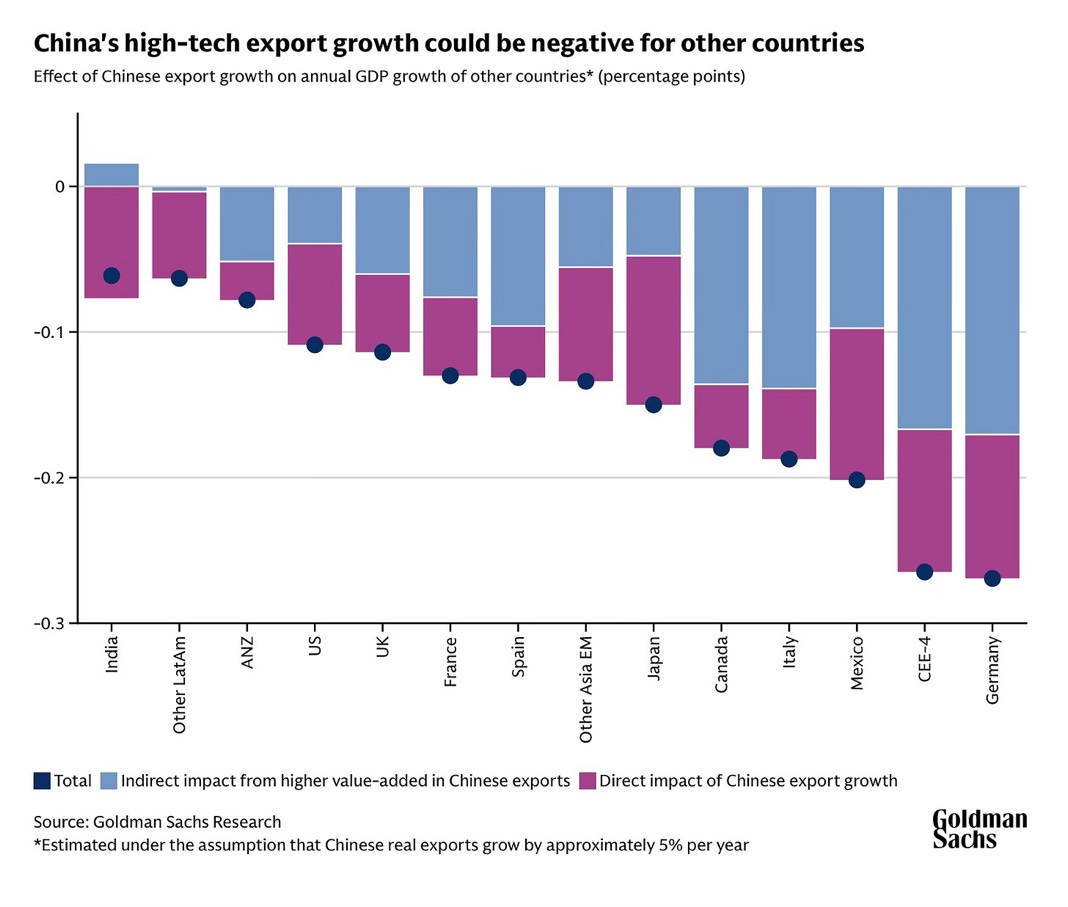

China’s Gain = Your Manufacturers’ Pain

There are benefits to being able to buy imported products more cheaply, of course. But for domestic competitors, it’s a big problem. Crucially, China’s beggar-thy-neighbour growth is now coming at the expense of growth elsewhere. This is what the Second China Shock looks like, from a new Goldman Sachs report recently cited in Greg Ip’s Wall Street Journal column:

Source: “China’s Economy is Forecast to Grow Faster Than Expected in 2026”, Goldman Sachs, 21 November 2025

Goldman forecasts Chinese GDP growth will accelerate by 0.6% annually, in the process reducing the rest of the world’s growth by 0.1% through deindustrialization and crowding out. It says “for 1 percentage point of export-driven boost to Chinese GDP, other economies may see a 0.1 to 0.3 percentage point drag, with high-tech producers like Europe and Japan facing particularly acute pressures… ‘China Shock 2.0’ may crowd out tech-intensive, high-value-added manufacturing.” Without even getting into the implications for society, politics and national security, this upends the traditional neoliberal economic wisdom that importing cheaper goods offsets losses from deindustrialization and delivers a net benefit to the economy. Moreover, state-backed Chinese firms that don’t need to make profits will also deny their foreign competitors the returns needed to invest to drive future productivity and innovation.

Trump’s Trade Deflection

For a deep dive on China Shock 2.0’s impact on the US, read the USCC’s new annual report to Congress, Chapter 8, which says: “as China floods global markets with its goods, it will gain a more dominant share of key markets, gutting foreign competitors and propelling them into a downward spiral of deindustrialization. This in turn will lead to greater control over critical supply chain chokepoints.”

Source: “Trade With China Is Becoming a One-Way Street”, Wall Street Journal

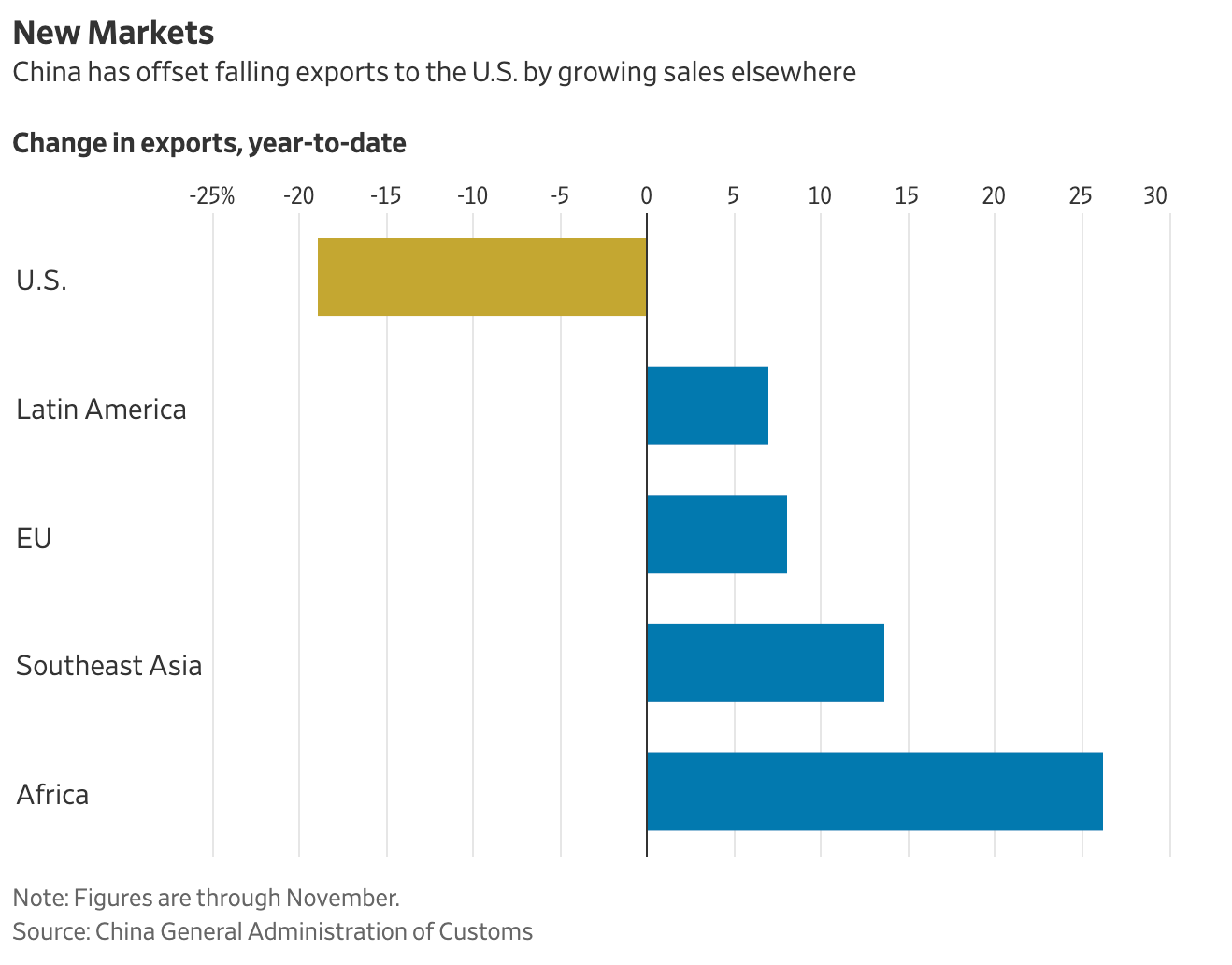

Donald Trump’s extraordinary tariff hikes this year are not only raising prices in the United States, they’re also constricting America’s role as global consumer of last resort. It’s buying less from China. Check out this Times interactive to see who’s absorbing the surplus. Short answer: everyone else, as the bar chart below shows.

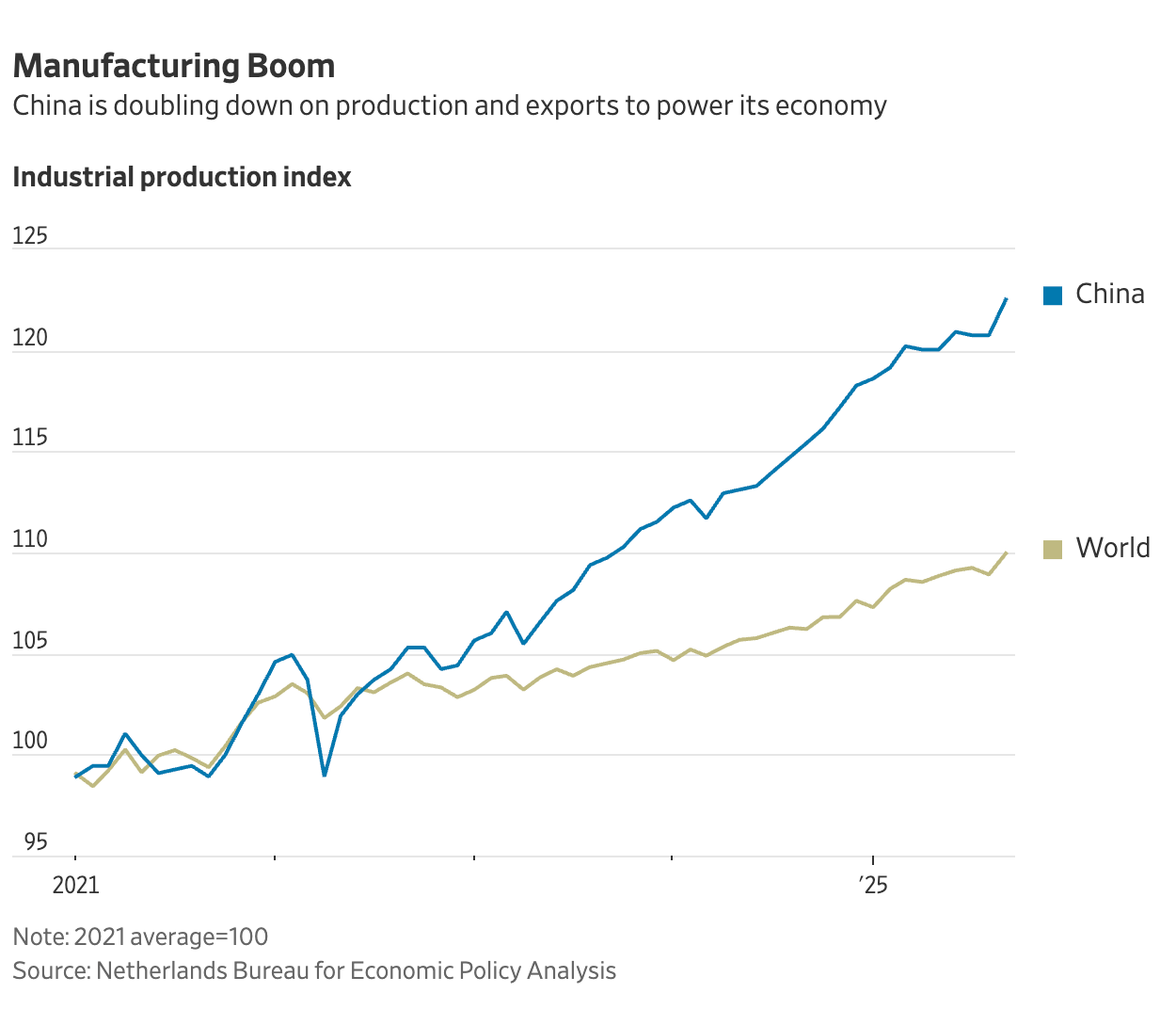

Source: “China’s Manufacturing Is Booming Despite Trump’s Tariffs”, Wall Street Journal

China is Eating Europe’s Industrial Lunch

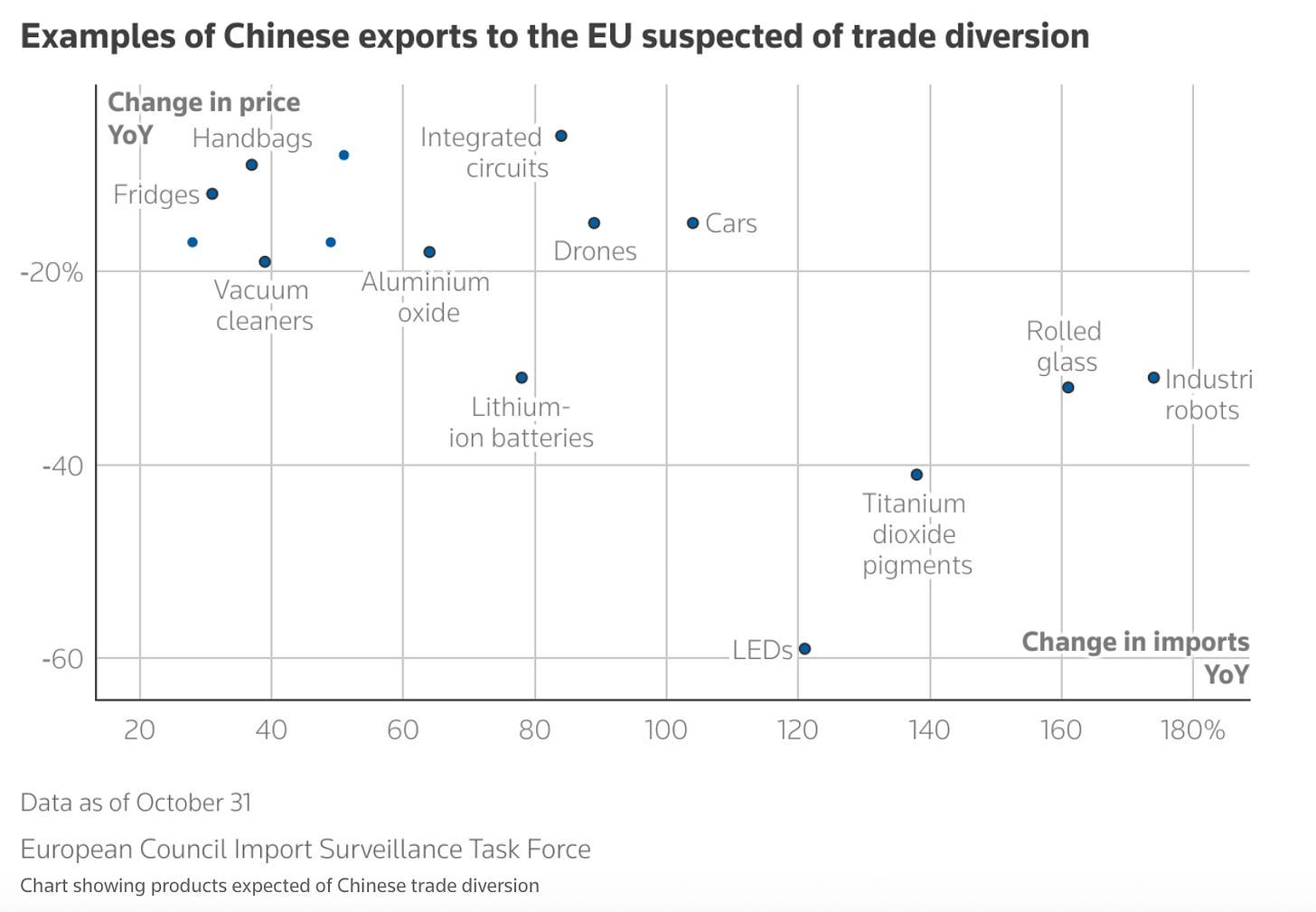

This is not just a US-China fight. “China now sells more than twice as much to the European Union as it buys,” Keith V Bradsher notes. In Europe, it’s set to crush an industrial core of automotive, machinery, and high-tech equipment makers. “The numbers are stark,” notes Reuters columnist Joachim Klement. “Over the last 12 months through October, imports of industrial robots from China have risen 171%, while prices fell 31%. Imports of integrated circuits are up 84%, with prices down 6%. Car imports have more than doubled while prices dropped 15%.”

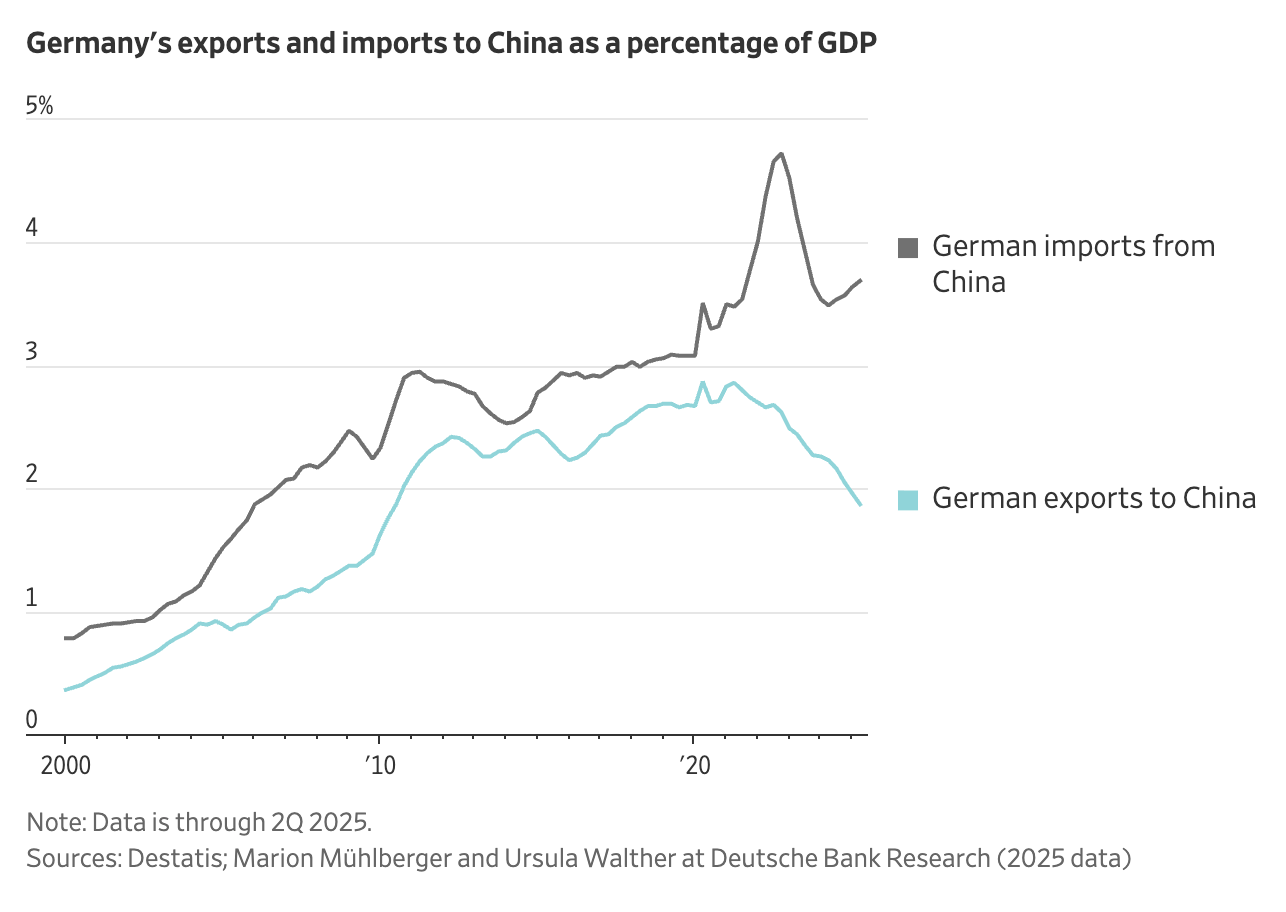

Germany has been a prime target “first as a source of technology, second as a partner through which to export standards favourable to China, and third as a competitor for the lead in the current industrial revolution,” warned a key 2020 report from FDD. “Germany is, in fact, a template for the CCP strategy to dominate the 21st-century economy and set the rules for the modern world,” it concluded. The situation has only grown worse since then, as Andreas Fulda explains in his book and a RUSI commentary. In October 2015, Germany ran a US$630 million trade surplus with China. In October 2025 it had a US$1.78 billion deficit, a swing of 338% over the decade.

Source: Why Germany Wants a Divorce With China, Wall Street Journal

Finbarr Bermingham reports Germany’s industrial sector is losing 10,000 jobs a month, and the national mood is bleak as its trade deficit with China soars. Thewirtschaftswunderis becoming awirtschaftsblunder. “In order to protect national sovereignty, increase industrial competitiveness and strengthen democratic resilience, some form of disentanglement is in order,” Fulda urges.

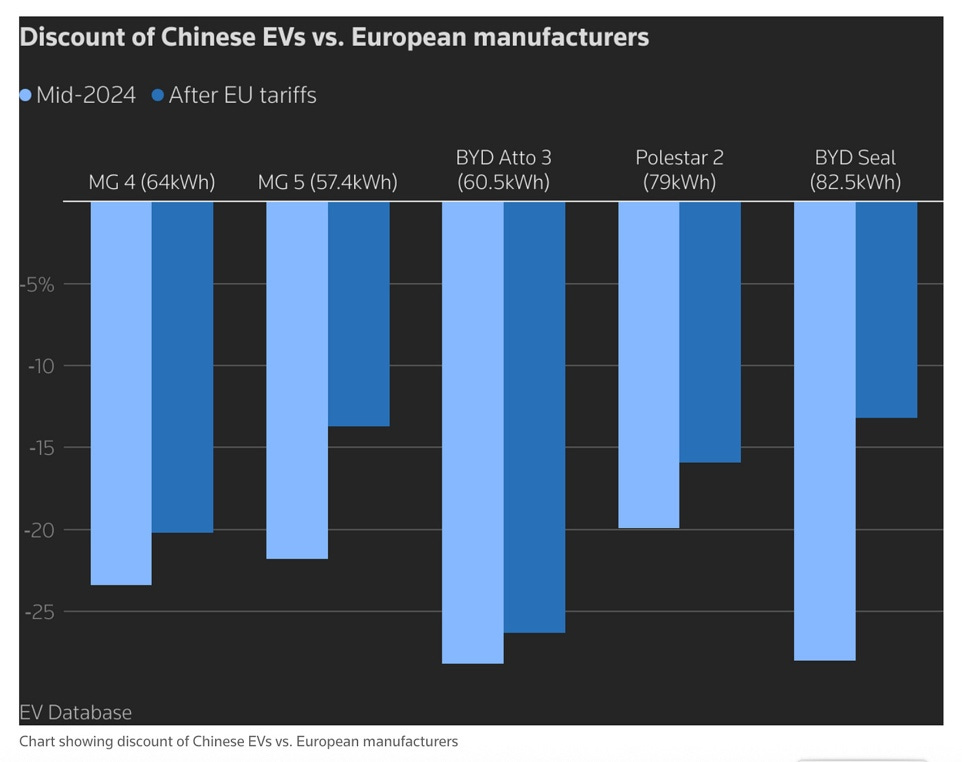

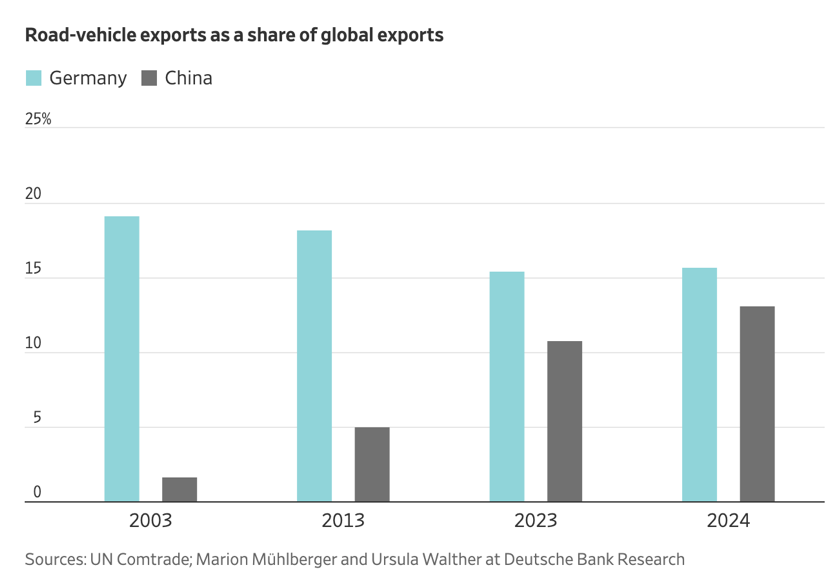

Automotive expert Michael Dunne reports that Chinese electric vehicle manufacturing is marching into Europe and gutting Western automakers. The EU has imposed various tariffs on Chinese EVs. That’ll be enough, right? Wrong. Look at the bar chart below. They’re not high enough to level the playing field. Moreover, they do nothing to stop European firms’ loss of export markets to Chinese competitors.

Why has Europe been so passive in response? Because its elites are divided, as GMF’s Noah Barkin explains in the latest edition of his indispensable “Watching China in Europe” monthly newsletter. He outlines three schools of European thought and paths for how the relationship could evolve: (A) decisively derisk, diversify and deploy all economic policy tools to force China to rebalance the relationship; (B) give in to short-term opportunism and gobble any crumbs China leaves behind in both markets; and (C) a muddled, half-assed mix of the two, with more talk than walk, while China divides and rules, and the outcome is the same as (B) but takes longer. Obviously, I’m arguing for Plan A. Paris sounds ready. Berlin is fumbling for a kaffee. The bureaucratic baristas in Brussels need to caffeinate the Continent faster.

Flooding the Global South

For developing countries, it’s no picnic either. For example, as Robin J Brooks points out, growth in Chinese EV exports leans heavily on the Global South. Dunne warns that “Chinese cars are pouring into Mexico” and its tariffs haven’t stopped them so far. EV imports are forecast to top 500,000 this year. This week Mexico announced tariffs of up to 50% on cars, clothing, appliances, plastics and more from China and other Asian exporters, effective from January.

This is a global problem sparking a global backlash, the WSJ notes. James Kynge says China’s breaking the rules of global development.

In a triple threat for emerging markets hoping to climb the value chain, General Secretary Xi Jinping insists that even as China reaches the commanding heights of high-tech manufacturing, it must:

1. continue mass low-end manufacturing,

2. restrict tech transfer to foreign enterprises, and

3. keep favouring industry and exports over measures that would boost consumption and imports.

Why? Because, as Xie Yanmei explains in the FT, “China’s political-economic system cannot countenance scattering resources for individual consumption. A defining feature of such a regime, with a Leninist core, is the mobilisation of resources for social-economic transformation….” The CCP looks at the West and sees “deindustrialisation, over-financialisation, destabilising booms and busts, social atomisation, populist ferment…” and prefers “to mobilise resources to power the ‘real economy’, synonymous in China with manufacturing.

Source: “China’s Manufacturing Is Booming Despite Trump’s Tariffs”, Wall Street Journal

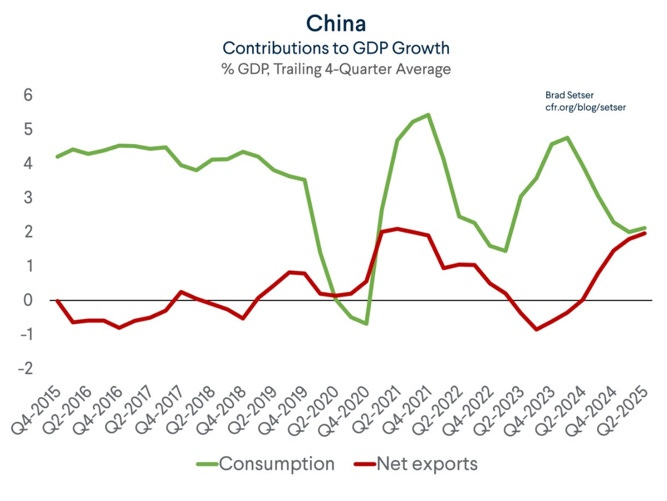

As Greg Ip correctly observes, the CCP doesn’t believe in balanced trade or comparative advantage. The economist Brad Setser sums it up its philosophy as exporting without importing. Setser also points out that since China joined the WTO, its manufacturing imports have actually declined as a share of its growing economy.

Industrial Completionism

That’s because the CCP’s goal is self-sufficiency through “Dual Circulation” and “Made in China 2025”, creating a “complete” industrial system in a solipsistic, strategic and ideological quest to preserve Party rule, boost Comprehensive National Power and make the PRC sanctions-proof so it can absorb Taiwan, bully its neighbours and face down Trump in trade wars without fear of the sort of repercussions Russia is currently weathering.

Dan Wang describes this in his new book Breakneck as a kind of “completionist” ideology: Xi wants China to be able to make everything itself on its march toward the “great rejuvenation” of the Chinese ethnostate by the year 2049. The Qing emperors would have approved. Likewise Mao. Xi’s ideology remains essentially communist, as he himself defines it.

For decades, the CCP has been enmeshing China’s heavily planned economy within a global system that it exploits and undermines. Essentially, the state takes money from the people through various means and gives it to companies, enabling them to export products at prices that undercut competitors. As that already enormous manufacturing capacity expands, the Party-state is counting on exports to absorb the surplus. The problem is becoming structural.

Antisocial Disruption

The IMF’s chief said Dec 10 that China is too big to base further growth on exports and is long overdue to change its economic model. The IMF recommends strengthening China’s social safety net. But the CCP doesn’t want to because Xi thinks consumers waste money and “welfarism” makes the people lazy when it wants them to work overtime for national greatness. After seeing ballooning entitlement spending cripple Western government balance sheets, he’s intent on avoiding the same trap. So don’t expect the Chinese consumer to ride to the rescue.

How about the property market? Again, no, property sales have been systematically declining since 2021. Xi has chosen not to rescue the property market and divert support away from manufacturing.

The CCP’s success in convincing some foreign liberal and social democratic politicians and others with left-wing political views that it has a fraternal devotion to socialism must be one of the greatest cons in history.2 Its Leninist creed is authoritarian state capitalism.

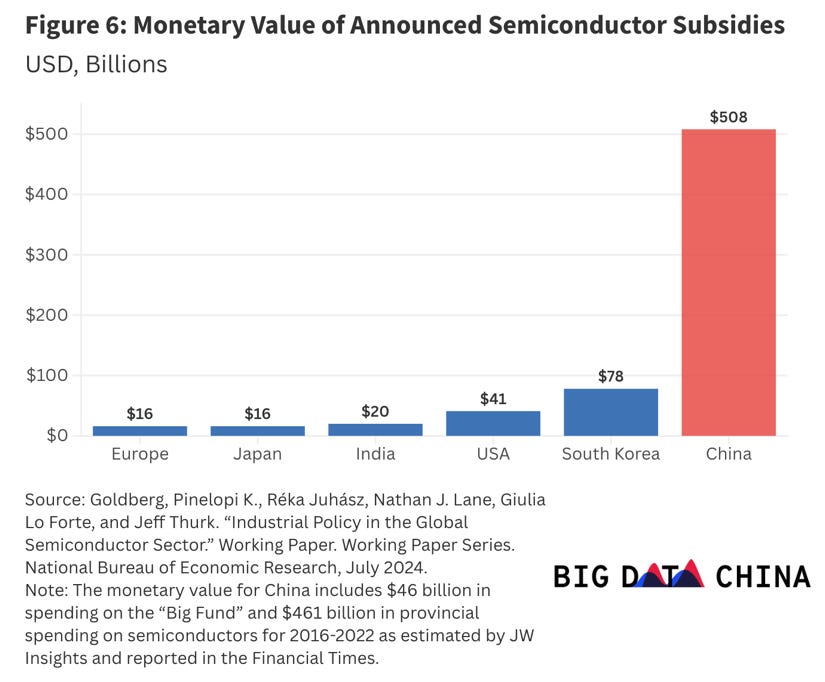

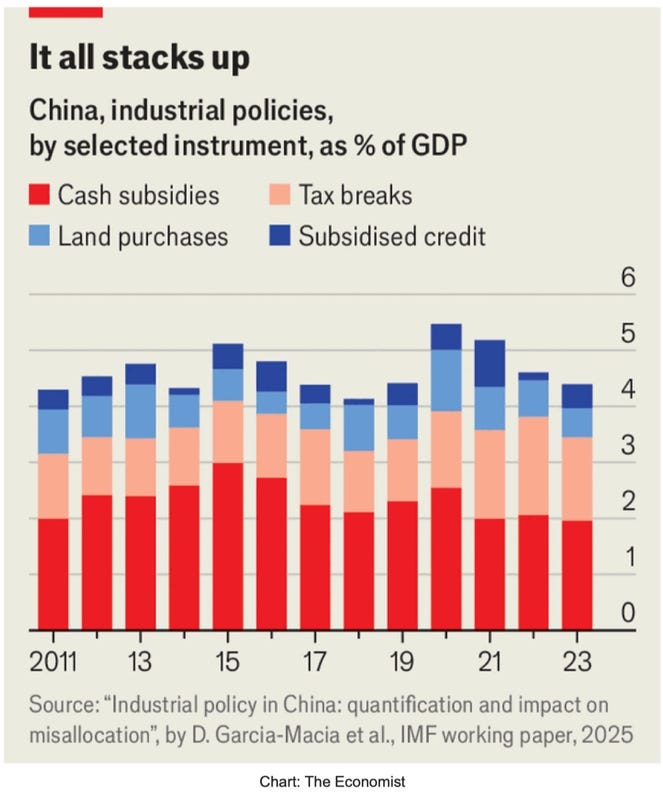

It’s critical to understand the sheer scale and complexity of PRC industrial intervention and market distortions. Boffins can dive into reports from CSIS, Rhodium Group, and MERICS. For a thin-slice, glance at these two charts from CSIS Big Data China:

And this from a recent IMF working paper that calculates PRC government support for target industries may exceed 4% of GDP—far more than any other country:

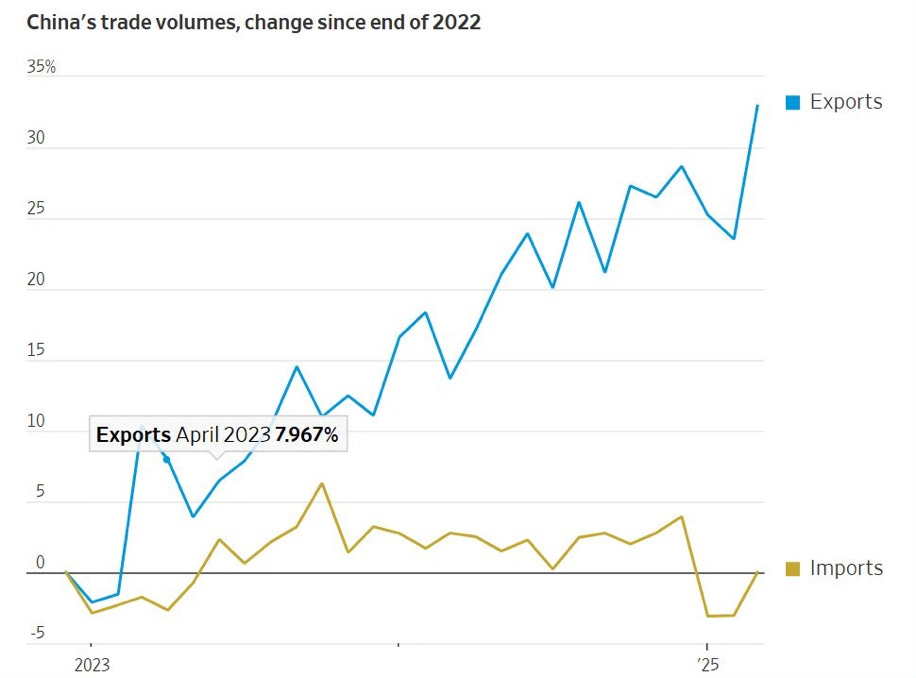

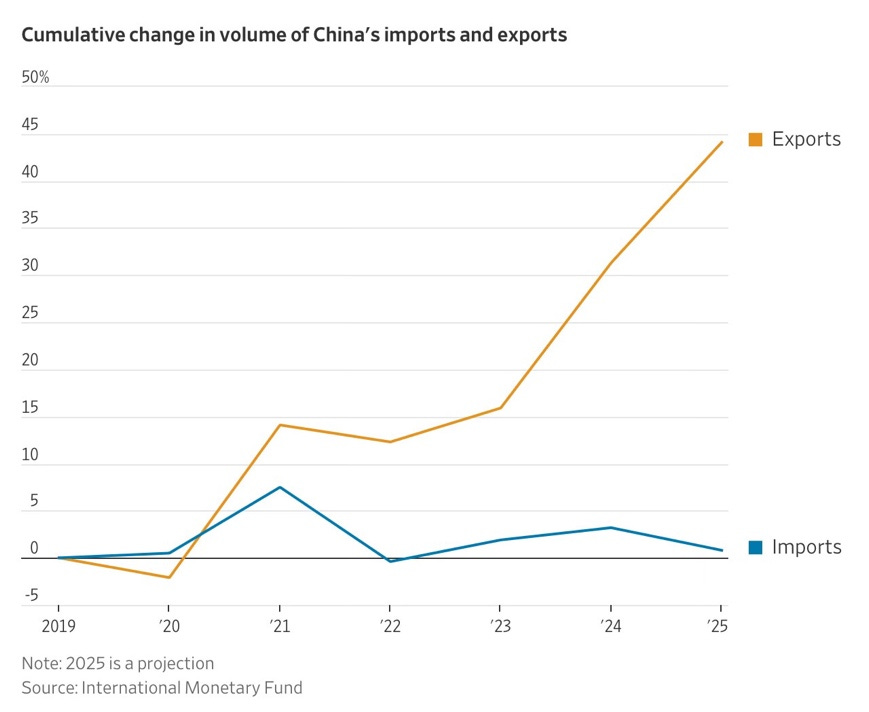

Result: China’s manufacturing exports have surged since 2018, while manufacturing imports have declined since 2023. The two are going in opposite directions. As a recent Gavekal Dragonomics note puts it, “China is no longer a growth market for what most Western economies have to sell.” Hence, it’s not a viable substitute for US demand for most goods.

Source: “China’s Growth Is Coming at the Rest of the World’s Expense”, WSJ

Moreover, there’s no end in sight. As economists such as Natixis’ Alicia Garcia Herrero forecasts, China’s macro outlook of lower growth and plummeting population does not bode well for a rebalancing towards imports and consumption. Nor does its refusal to adjust its currency’s exchange rate. The IMF, Goldman Sachs and others reckon a cheap yuan (renminbi) is exacerbating the problem.

A handful of commodity producers like Australia, Brazil, Canada, and the US have benefitted from growing Chinese imports in food, raw materials and energy (e.g. oil, canola, soybeans, and minerals). And its demand for a few commodities like iron, copper and energy may continue to expand, but most other commodity import growth will likely soon run out of road as the structure of China’s GDP shifts away from infrastructure investment and its population ages and shrinks.

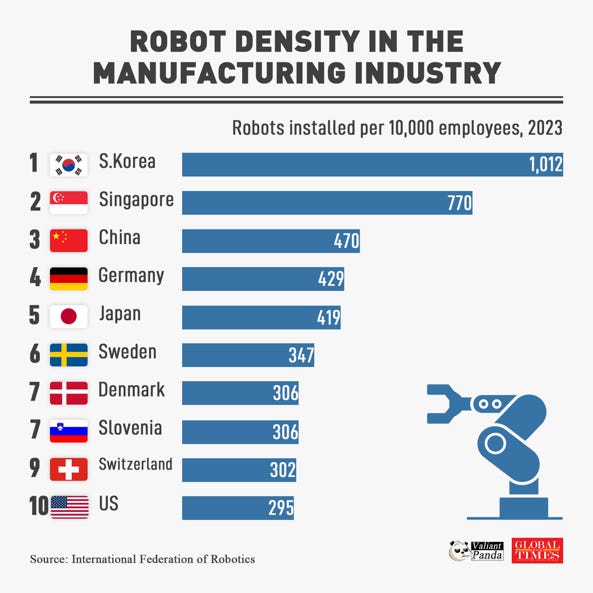

China now leads the world in total number of active robots and surpasses Germany and Japan for robot density. Its production of robots this year is up nearly 30% and accounts for around half of new global installations. They’ve already displaced 14% of China’s workers. Robots are great at making exports, lousy at consuming imports: they don’t fry tofu with canola oil in imported woks while sipping cognac.

This is Why We Can’t Have Cheap Nice Things

But wait, why can’t we just enjoy cheap stuff from China and not worry about making things ourselves? Because, as Autor, Dorn, and Hanson demonstrated in their research on China Shock 1.0, job destruction brings community disruption, which leads to political problems. It’s a big part of how we got into the current mess.

“The social consequences of the second China shock around the world are likely to be as profound as the first in the West,” the NYT writes. “We’re starting to get a glimpse of what they might look like.” They look like anemic economic growth, disappearing jobs, rising instability, social discontent, political polarization, and populism.

Shouldn’t we welcome cheap solar panels, batteries and more from China to mitigate climate change? Too simple. It’s political economy 101: if there’s no domestic business constituency to support the green transition, it won’t be durable. As Paul Krugman writes, “If those subsidies are seen as creating jobs in China instead, our last, best hope of avoiding climate catastrophe will be lost — a consideration that easily outweighs all the usual arguments against tariffs.” In a world where China is building over 90% of all new coal plants, progress toward net zero has to be balanced with preserving industries and decent jobs. Reality bites.

Mercantilism with Chinese Characteristics

Backed by China’s scale, the Party’s mercantilist policies are deindustrializing advanced economies and erecting barriers to poorer countries ever industrializing. Is the CCP doing this deliberately to weaken Western rivals and suppress their defence industrial bases, or is it just an unintended negative externality of its own political economy and production-centric ideology? Is it just trying to make China run faster, or also kneecap opponents? Given how secretive it is, until we have access to its internal files, that will be debatable. But it certainly seems to regret publicizing “Made in China 2025”.

My hypothesis: it’s a self-inflicted structural problem that the CCP is opportunistically weaponizing. Once it has overcapacity, the PRC government guides and uses it in ways that increase foreign dependence and constrain foreign firms’ market share and ability to produce in key sectors. Add to that its propensity to impose supply chain chokepoints on things like rare earths for coercion and you have a powerful playbook for using economic dependence for leverage.

The CCP’s response? Denial, of course. Its propaganda organs have been running commentaries “debunking” the “myth” and “concoction” of a Second China Shock, and likening it to another bogus “China Threat Theory”. Pro tip: never believe anything until the Party-state denies it.

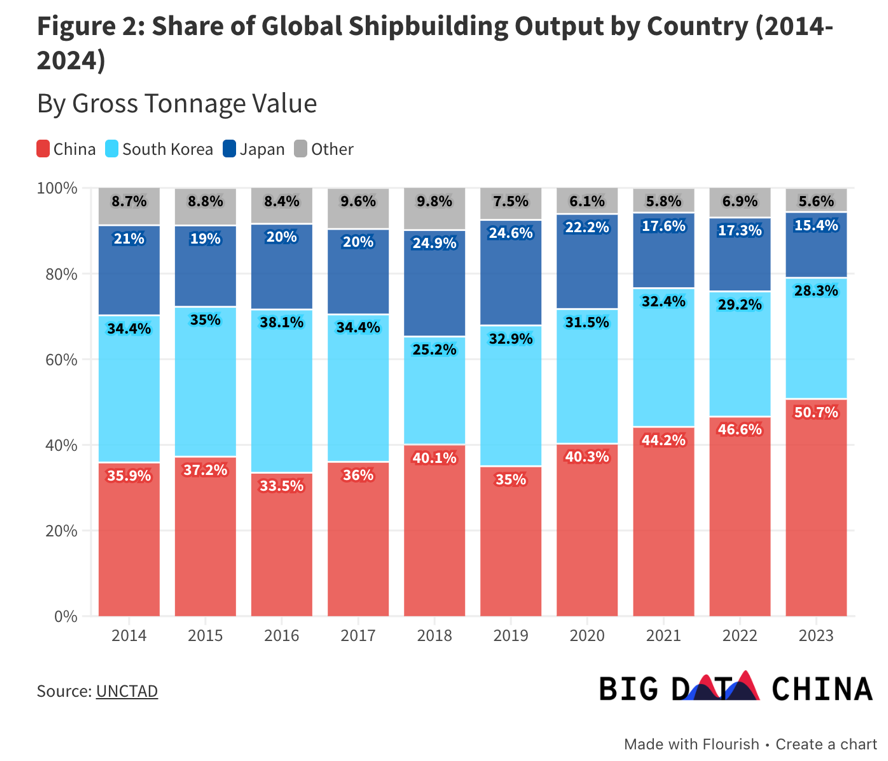

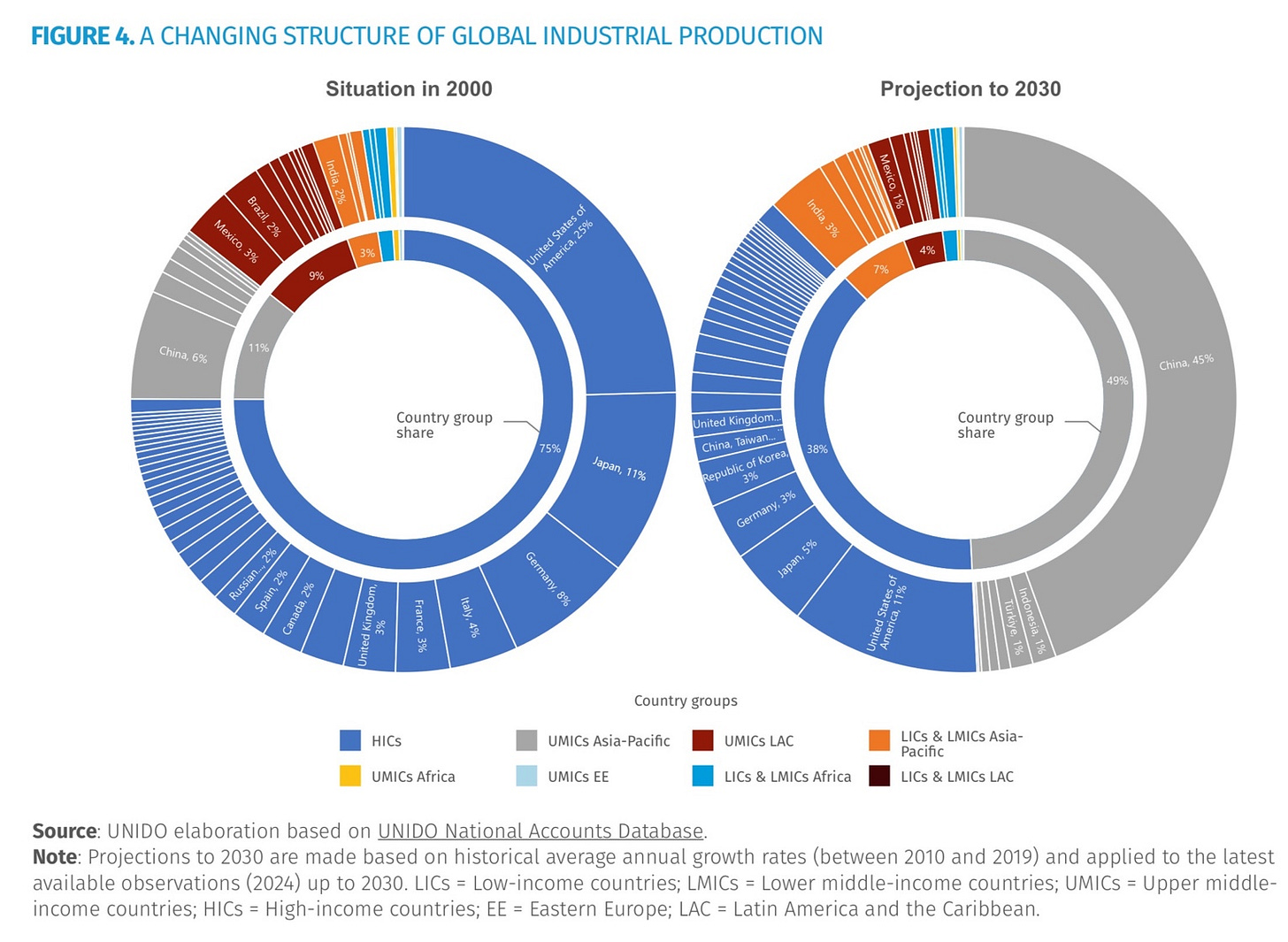

As Noah Smith wrote last year, manufacturing is a war now. And, Sam Olsen adds, China is rewriting the industrial playbook Britain invented. Check the pie chart below. Is this the future we want?

For policymakers today, both in developed and developing countries, does it matter whether it’s a PRC strategy or only tactics? Either way, it’s essential to act—decisively, comprehensively, and swiftly. In that regard, it’s notable that both the new US National Security Strategy and EU economic security blueprint give heavy emphasis to the intersection of economic statecraft and security. As they emphasize, increasing supply-chain resilience and diversifying trading partners matters more than ever. So does coordination.

Robin Harding in the Financial Times is crystalline: “China is making trade impossible. If it will buy nothing from others but commodities and consumer goods, they must prepare to do the same.”

Excerpted with edits: https://michaelkovrig.substack.com/p/china-shock-20-is-coming-for-your?r=lah31&utm_medium=ios&triedRedirect=true

The MIT Initiative for New Manufacturing (INM) aims to redefine what’s possible in manufacturing. Through research, hands-on training, and deep industry collaboration, INM aims to build the tools, systems, and talent to shape a more productive, sustainable, and resilient future. INM is a campus-wide manufacturing effort directed by Professors Suzanne Berger, A. John Hart and Christopher Love that convenes industry, government, and non-profit stakeholders with the MIT community to accelerate the transformation of manufacturing.

MIT’s Bill Bonvillian and David Adler edit this Update. We encourage readers to send articles that you think will be of interest to us at mfg-at-mit@mit.edu.

Subscribe to the MIT Initiative for New Manufacturing Substack

Insights from articles and reports of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad