Manufacturing Update - 23 July 2024

Insights from articles and reports of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad

“Manufacturing Update” is planned as a periodic newsletter summarizing a small collection of recent articles on manufacturing technology, management, economics, and policy developments in the US and abroad that we think will be of interest.

The concept is to update the group on manufacturing developments that may be of interest, to share ideas, and to promote fluency and expertise with manufacturing issues and the debates around them. We encourage readers to send articles that you think will be of interest to us at mfg-at-mit@mit.edu.

The Mysterious Slowdown in US Manufacturing Productivity

Investing in Productivity Growth

Why Can’t the US Build Enough Weapons?

China’s AI Industrial Chain

What the EU can learn from its EV Anti-Subsidy Investigation against China

1. “The Mysterious Slowdown in US Manufacturing Productivity,” Danial Lashkari and Jeremy Pearce, Liberty Street Economics, New York Fed, July 11, 2024

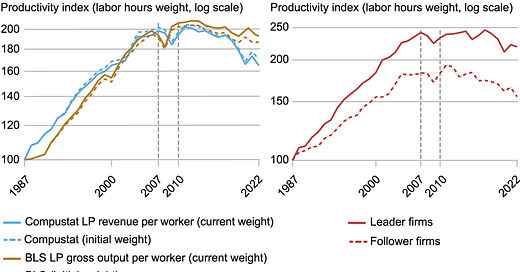

Historically, the long-term US labor productivity rate was steady at around 2%. However, for the past two decades productivity in the US has slowed down. This has been particularly stark in the manufacturing sector, even though manufacturing accounts for more than half of US R&D expenditures and historically led productivity growth. The slowdown appears pervasive across all manufacturing industries and affects firms of varying sizes. This has become a critical issue in US long term growth. See chart below:

Manufacturing Productivity Slowdown Stems from Productivity Slowdown at the Firm Level

2. “Investing in Productivity Growth,” McKinsey Global Institute, March 20, 2024

The report notes the relationship between labor productivity and capital investment; slowing or stagnating productivity in advanced economies parallels slowing capital investment. As the charts below show, China and India account for half of world productivity growth from 1997 2022 and made corresponding increases in their capital investment per worker.

For more: https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/investing-in-productivity-growth

3. “Why Can’t America Build Enough Weapons?” Mike Lofgren, Defense Tech and Acquisition News, July 6, 2024

Defense manufacturing is falling short. Ukraine continues to be the best “canary in the coal mine” for how the DoD needs to transform its industrial base. The DoD needs to scale its technologies much faster and use private capital markets for investment, to rebuild its industrial base. In the past, the US excelled above any other nations in the sheer quantity of defense materiel that it could produce, and in its superb logistics system that could get material where it was needed on time.

During WWII, the Ford Motor Company constructed a bomber manufacturing facility with an assembly line more than a mile long that could produce a B-24 every hour. This demonstrated that the “Arsenal of Democracy” was not a mere propaganda slogan. Eighty years later, America’s arsenal is in much the same shape as the remains of the Ford plant: underutilized for decades and gone to seed. To cite points from the article:

The U.S. has transferred more than 3 million 155 mm artillery rounds to Ukraine. Current annual production of the 155 round is about 12% of that amount.

Even with a currently planned surge in production to restore stocks, it will require several years to rebuild the inventory because of the lead time needed to set up new manufacturing capability.

M6 propellant is no longer produced in the U.S., nor does the military have a single TNT plant for the explosive. Until it can reestablish domestic production, the Army will have to rely on allies like Poland and Australia.

Russia, with 1/10 the GDP purchasing power parity of the U.S. and the EU combined, can produce nearly three times the number of artillery rounds.

It is estimated that expended units of the Javelin antitank missile will require five and a half to eight years to replenish; the HIMARS guided rocket, two and a half to three; the Stinger antiaircraft missile, six and a half to an incredible 18 years.

The 10 largest defense companies in the mid-1980s were McDonnell Douglas, General Dynamics, Rockwell, General Electric, Boeing, Lockheed, United Technologies, Hughes, Raytheon, and Grumman.

By 2000, the top tier was reduced to five: Boeing, Lockheed Martin, General Dynamics, Raytheon, and Northrop Grumman.

Most of these resulted from mergers with other large defense companies, reducing both capacity and competition. This has led to an oligopolistic concentration: In 2023, the top six DoD contractors received almost $200B in revenue in the defense business, with much smaller figures booked by all the rest.

The Navy is in a protracted, slow-motion crisis: America’s shipbuilding base has shriveled to virtually nothing, while its aging workforce retiring.

The Navy has apparently forgotten how to design and build ships: The Zumwalt-class destroyer and the Littoral Combat Ship have been unmitigated disasters.

No commercial shipbuilding means no production facilities or skilled labor that the U.S. Navy could use in a surge. No operating subsidies mean no reserve of American mariners for ocean transport to overseas theaters.

A 2023 CRS report noted that 37% of the Navy’s attack sub force is unavailable for service, and that the problem is expected to worsen.

After building three Zumwalt-class destroyers for $22.5B, the Navy cancelled the program when it stumbled on the fact that the gun—around which the entire ship had been built—used ammunition that was too expensive to use on a wide scale. The three completed hulls are still searching for a mission.

Each Navy Littoral Combat Ship ended up costing more than twice the original estimate and are now being retired at less than half their projected 25-year service life.

9/11 and the subsequent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan expended $1.5T on counterinsurgency operations, paid in part with deep cuts in many traditional weapon systems.

The National Defense Stockpile went from a value of $9.6B in 1989 to $888M in 2021. The Defense Logistics Agency reported <10% of postulated wartime material shortfalls are mitiygated.

The Air Force’s aircraft mission-capable rates have stagnated for years in the low 70% range—well below what would be needed in a crisis, particularly as the size of the aircraft fleet has steadily declined for more than 30 years.The Army spent $32B on programs related to its Future Combat Systems program with little to show for it.

For more (paywall): https://defenseacquisition.substack.com/p/defense-tech-and-acquisition-news-99a; for longer version see: https://washingtonmonthly.com/2024/06/23/why-cant-america-build-enough-weapons/

4. “China’s AI Industrial Chain,” a/symmetric-Force Distance Times, July 6, 2024

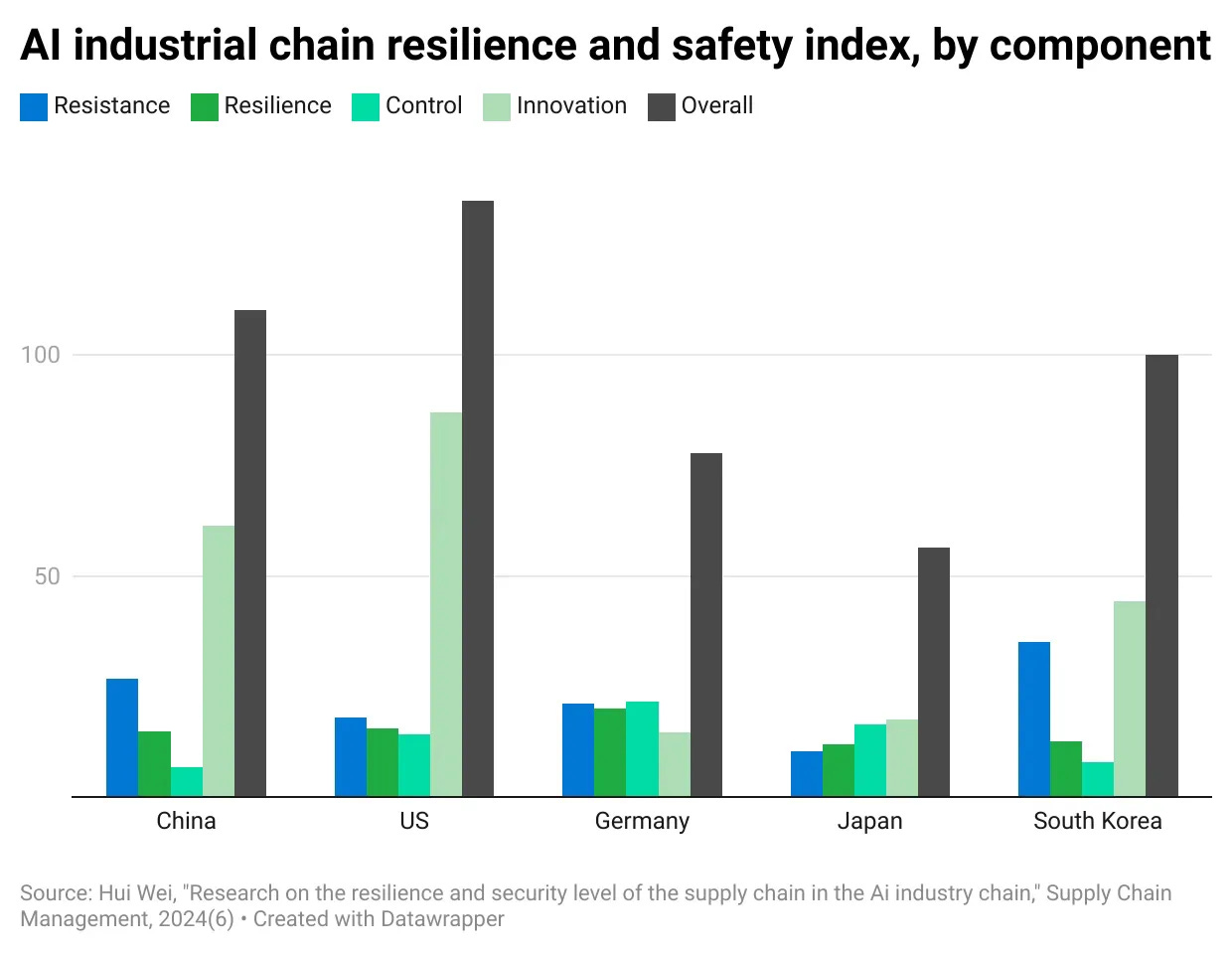

A new index from Hui Wei (see chart below) measures the safety and resilience of different countries’ AI industrial chains. Her calculations put the US in the global lead, with China quickly catching up and surpassing incumbents including Japan, Germany, and South Korea. Looking at the index’s four major subcomponents — resistance, resilience, control, and innovation — gives us a more detailed view where China is currently most vulnerable in the AI domain, and where it might gain asymmetric advantages.

Notably, among the five countries Hui assesses, China ranks lowest in control over its AI industrial chain. To measure control, she looked at a country’s dependence on foreign chips; its high-tech products as a share of manufactured exports; and the ratio of expenditure on to income from intellectual property royalties; China is particularly weak in dependence on foreign chips.

China fares better in the “resistance” component, ranking second versus America’s fourth place. Hui measures resistance, or ability of a given country’s AI industrial chain to resist external shocks, by looking at two factors: imports of computers and telecommunications equipment as a share of overall imports; and national deployment of industrial robots. While the most salient crimp on China’s AI capabilities appears to be its foreign chip dependence, the country has multiple other avenues for shoring up its AI industrial chain.That includes investing in industrial AI to complement its existing manufacturing dominance, and building out “AI factories” and playing to China’s strengths in rolling out infrastructure at scale. The US, for example. is has had growing weakness in high tech exports as a percentage of manufacturing exports.

In other words, China’s struggle to procure enough advanced chips is only one part of the story — and may mask other ways in which the country is amassing strategic advantages in the AI domain. That has implications for how other countries compete in this emerging and rapidly shifting field.

For more:

5. “Boxing Smartly by the Rules: What the EU can learn from its EV Anti-Subsidy Investigation against China” Arthur Leichthammer and Nils Redeker, Jacques Delors Center (Berlin), Policy Brief, July 2024

Given China’s emergence as the world’s leading auto exporter overall and its dominance in EVs, the EU’s anti-subsidy investigation into Chinese EV exports is its most significant in years, with the potential for far-reaching economic consequences. The politics of trade defense are becoming both contentious and more complex. To cope with these realities, the EU should take three lessons from the investigation. First trade defense should be rules-based but strategic, concentrating on sectors where the EU has significant economic interests to protect. Second, the measures should be effective but keep the door open for competition. And third, these measures need to be embedded in a much more forceful European industrial policy strategy. This includes incentives to create a reliable EV market for producers, such as robust policies to de-risk and scale manufacturing projects in the EV supply chain, better support for risky technologies from the European Investment Bank, and public procurement of EVs.

Since 2022, MIT has formed a vision for Manufacturing@MIT—a new, campus-wide manufacturing initiative directed by Professors Suzanne Berger and A. John Hart that convenes industry, government, and non-profit stakeholders with the MIT community to accelerate the transformation of manufacturing for innovation, growth, equity, and sustainability. Manufacturing@MIT is organized around four Grand Challenges:

1. Scaling advanced manufacturing technologies

2. Training the manufacturing workforce

3. Establishing resilient supply chains

4. Enabling environmental sustainability and circularity

MIT’s Bill Bonvillian and David Adler edit this Update.