Manufacturing Update - 10 July 2025

Insights from articles and reports, excerpted and summarized, of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad.

Content:

1. THE BIG BEAUTIFUL BILL AND MANUFACTURING: “Trump’s Megabill: What’s in it for Manufacturers?”

2. THE WHY OF THE NIPPON-US STEEL DEAL: “The Japanese Bought US Steel”

3. CHIPS ACT REDUX: “Lutnick Says Commerce Department is ‘Renegotiating’ CHIPS Contracts”

4. CRITICAL METALS: “Nth Cycle is Bringing Critical Metals Refining to the US”

5. CHINA’S CHOKE POINTS: “The Vulnerabilities Holding Back Chinese Industry”

6. EAT DUST? “How China’s New Auto Giants Left GM, VW and Tesla in the Dust”

7. HISTORICALLY, WAGES ARE UP: “American Wages really Have Gone Up”

1. THE BIG BEAUTIFUL BILL AND MANUFACTURING

“Trump’s Megabill: What’s in it for Manufacturers?” Nathan Owens, Manufacturing Dive, July 2, 2025

Here are the highlights from the bill that manufacturing groups believe would benefit them:

Creates a new deduction allowing companies to expense the cost of new factories and improvements to existing facilities.

Permanently restores expensing for research and development and capital equipment purchases, as well as the interest deductibility standard.

Permanently extends the 20% pass-through deduction for small firms for qualified income and preserves the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) individual tax rates.

Expands and makes permanent the TCJA estate tax exemption.

Preserves the 21% corporate tax rate.

Upholds the TCJA’s international tax system by making the Act’s treatment of FDII (Foreign Derived Intangible Income, for income earned by US firms from sales to foreign customers), GILTI (Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income, which targets income earned by a firm’s foreign affiliates) and BEAT (Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax, to prevent US firms from avoiding domestic tax liability) permanent.

Increases the Section 48D advanced manufacturing investment tax credit for firms that invest in advanced manufacturing, particularly semiconductor manufacturing and equipment.

Excerpted with edits: https://www.manufacturingdive.com/news/trump-megabill-final-stages-of-debate-manufacturing-highlights/752231/

2. THE WHY OF THE NIPPON-US STEEL DEAL

“The Japanese Bought US Steel,” Jon Y, Asianometry, July 6, 2025

US Steel: US Steel has this long, illustrious history filled with America's most famous titans of industry. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, US Steel undergoes massive site closures and job cuts to become a competitive company once again. By 2000, the company has reduced its once-sprawling production US footprint to just three big sites: Gary Works, Mon Valley, and Fairfield. There are a few minor sites for finishing or ore work but those three are the big American ones. Despite its slimmed down profile and greatly improved productivity, the company struggles through the 2000s and 2010s amidst a global steel glut and weak economic demand. Much trouble can be attributed to the strength of the Minimills.

Minimills use electric arc furnaces and continuous casting to melt down scrap steel for new steel bars, sheets, or strips. US Steel on the other hand has been an integrated steel producer throughout its long history. This means owning all the major facilities that turn iron ore and coking coal into crude steel - notably the coking ovens to produce coke and blast furnaces to make pig iron. Minimills are more flexible, use 30% less energy, put out 90% less emissions since they rely on electricity, and can be built cheaper and closer to where their end users are. They are the canonical example of technology disruption, taking down the big integrated steel players in the 1970s and 1980s. Today, over 70% of the steel in the US steel market is made using electric arc furnaces. America's largest and most valuable steelmaker Nucor, for instance, relies on minimills and they make twice as much revenue as US Steel.

Strategy Shift: For a long time, US Steel stuck to its integrated approach. Then in October 2019, US Steel announced that they paid $700 million for a minority stake in Big River Steel - which was building a big, advanced minimill in Arkansas. US Steel thus changed its strategy to involve both integrated and minimill steel operations - a strategy called "Best of Both". A few years later, it seems like the acquisition is working. The Minimill segment - aided a bit by new tariffs in 2018 - has grown by providing "electrical" steels for the booming EV motor, automotive, and electrical equipment industries in the American south and Mexico. This stuff is pretty cool. US Steel calls it Indux, but it is an ultra-thin, very light non-grain oriented steel that does not heat up as much when exposed to changing magnetic fields. Useful anywhere electricity is being turned into motion or vice versa. So not just EV motors but also generators and transformers. Considering that the single biggest bottleneck in AI data center expansion is power, that's a pretty good area to be in. The Big River facility has now been expanded with a second unit. And going into 2025, nearly 40% of the company's steel is produced using electric arc furnaces. Sounds great and the stock loves it, but this burgeoning Minimill growth has created new tension with US Steel’s union, the United Steelworkers. US Steel's developing turnaround has brought buyers out of the steelwork.

Nippon Steel: At one time, the Japanese steel industry was the greatest in the world, with Nippon Steel its largest and mightiest company. I did a video about Nippon Steel's origins dating all the way back to the 1900s so feel free to watch that. Nippon Steel's most significant ancestor was a government-backed steel facility called Yawata Steel. In the 1930s, the government merged Yawata with other privately-owned companies to form Japan Iron & Steel, an integrated steel monopoly controlling both the iron and steel industries. This company was then split into two after World War II because of its participation in the Japanese war machine. But during a large steel glut in the 1960s, the two pieces merged together again in 1970 to form Nippon Steel. Complicated, isn't it?

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Japanese aggressively built greenfield steel plants in coastal areas. These plants were not only massive, but also employed the latest technologies like the Basic Oxygen Furnace. Their steel was often sold to Japanese automakers or exported abroad. In the mid-1970s, Japan by itself accounted for almost a third of global steel exports. This jubilant steel market peaked in 1973 with the energy crises. After that, the Japanese steel industry began declining as the world economy changed, new competition emerged (more on that later), the Plaza Accord re-valued the Japanese yen, and the domestic Japanese market plunged into a decades-long downturn. Nippon Steel aggressively managed the change with extensive job cuts (they went from 75,000 employees to just 15,000), cost reductions, shifts to higher value steel products, and business diversifications.

Nippon Transfers Its Technology: Those losses were nothing compared to another big Nippon Steel loss - their efforts nurturing foreign competitors. After the energy crises, the Japanese steel industry began exporting their steel technology and know-how to developing economies like Brazil and Taiwan. Many customers saw steel as a cornerstone of industrial policy and wanted their own steelworks. Japan taught them what they knew. The most egregious efforts were POSCO in South Korea and Baoshan Steel in the People's Republic of China. The deals were essentially efforts to better relations between Japan and those countries. But Nippon Steel gave the technology transfer a full and earnest effort. And it worked. Perhaps too well. As for China, before Nippon came along, Chinese steel production was hopelessly behind. It took 70 man-hours to produce a single ton of steel. With Nippon's complete and total system transfer, Baoshan Steel cuts that down to just 4, blossoming into Mainland China's most advanced steelmaker. They eventually absorb others to become Baowu Steel Group, the world's largest steel company today. In 2024, Baowu put out 130 million tons of steel, more than the second and third largest steelmakers combined.

China’s Growth Forces Consolidations: China's economic rise triggered a wave of consolidations up and down the steel supply chain. On the steel vendor side, the iron ore makers combined into global giants like Rio Tinto and BHP controlling over 70% of the world ore market. And then on the steel customer side, the big automakers - a critical steel user - were also consolidating. Now the top ten automakers control 80% of global car production. The steel companies have to size up to match with these new giants. An aggressive buyer led the way. Throughout the early 2000s, Mittal Steel - founded and run by the Indian steel magnate Lakshmi Mittal - had grown massive buying smaller steel makers around the world. In 2006, Mittal Steel launches a hostile bid for Arcelor Steel, Europe's largest steelmaker. After a vicious battle, Mittal succeeds, paying $34 billion to create the largest steelmaker the world had ever seen up until then: ArcelorMittal. The ArcelorMittal deal deeply shook the Japanese steel players, because it showed them that even they were not safe. The Japanese steel industry needed to get bigger to keep up with the rest. These thoughts led Nippon to merge with Japan's number three steelmaker Sumitomo in 2012. The new Nippon Steel quickly became the second largest steelmaker in the world, but has again lost share as the Chinese rise.

Why Nippon Wants US Steel: Over ten years later, the steel industry is poised for another wave of consolidation. The Chinese steel industry is in the midst of an immense glut. In August 2024, Baowu Steel Group's chairman Hu Wangming said that China's steel industry was in a "severe" crisis and a "harsh winter". In other words, there are still too many steelmakers in China. In 2022, the top 10 Chinese steelmakers made about 43% of the country's steel. The government wants to raise that ratio to 60-70%. You know where this goes. The harsh winter will be harsh, but it will eventually forge a cluster of ultra-competitive Chinese steelmakers with global ambitions. Nippon Steel needs to keep up with that, and Japan's domestic market is not enough. Vice Chairman Takahiro Mori has said, "Growth can be only expected overseas". Chairman and CEO Eiji Hashimoto has talked about creating an "iron triangle" between Japan, India, and United States. And the US picking up a more protectionist bent - i.e. tariffs - means establishing and growing a sufficient US beachhead inside the tariff wall.

In late August 2023, Nippon Steel signs a confidentiality agreement with US Steel, officially entering the horse race. In September they offer to purchase only US Steel's minimills and mining assets for $9 billion, but that was rebuffed. With Cleveland-Cliffs raising their offer, US Steel asks Nippon to buy the whole company. So Nippon Steel comes back with a very good offer. Right from the get-go, the optics of an iconic, 122-year old steel company being bought by - of all companies Japan's Nippon Steel - were not great. People have long memories. And in their minds, Japan and their cheap steel imports killed the Good Old Days. And even setting that history aside, people expressed concerns about a foreign country "owning" US Steel. Isn't steel really important? Isn't this a national security issue? For their part, the USW long ago announced that it exclusively favored Cleveland-Cliffs as the buyer. The two have a long working relationship.

The US President at the time Joe Biden had long supported unions. And Pennsylvania, the state where US Steel is headquartered, would be a critical swing state in the then-upcoming presidential election. In March 2024, the president says that he has concerns about the deal. Various senators and then candidate-Trump also say the same. For the workers, Nippon Steel adds sweeteners. One of which being a pledge to invest over a billion dollars into Mon Valley and $300 million into Gary Works. And I think that means a lot to the actual rank and file workers at Mon Valley, who are hopeful. But the USW upper ranks and US government remain unconvinced. In January 2025, shortly before leaving office, the outgoing president puts an executive order blocking the deal on national security grounds. In normal times, a death knell.

Beyond the politics and name-calling, the key issue is: What will most likely help the US steel industry modernize and expand capacity? There are questions about whether Cleveland-Cliffs, the competitor to Nippon, has the money to make the formidable investments needed to modernize US Steel's facilities. Cleveland's net income and return on capital ratios have been declining since 2021. Extensive investments upgrading older facilities Steel - plus buying Stelco for $2.5 billion in 2024 - has left the company with a heavy debt load in recent years. Earnings are weak and rating agencies are worried.

Thanks to some lobbying by people on both the American and Japanese sides, it seems like the new administration recognized several key issues. Steel is the sinew and skeleton of industry and manufacturing. And China has 13x more steel capacity than the United States. Nippon is offering to invest $11 billion more into steel plants on US soil to help close that gap. Nippon is motivated and has the money and technology to expand the US industrial base. The deal went back and forth for a while. Since they would be transferring their advanced proprietary steel technology, Nippon wanted 100% ownership. But the US government insisted on American "total control." In mid-June, Trump lifted the block and the acquisition - carefully characterized by Nippon as a "partnership" - closed shortly thereafter. On June 30, the deal went through.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://asianometry.passport.online/member/episode/the-japanese-bought-us-steel

3. CHIPS ACT REDUX

“Lutnick Says Commerce Department is ‘Renegotiating’ CHIPS Contracts,” Kate Magill, Manufacturing Dive, June 5, 2025

The Commerce Department is renegotiating some of the multibillion-dollar contracts to chipmakers funded by the CHIPS and Science Act, Secretary Howard Lutnick said during a congressional budget hearing. Lutnick said that he’s pushing for funding levels that amount to “4% or less” of a project’s total value. “A 10% funding just seemed overly generous and we’ve been able to renegotiate them,” he added.

Lutnick cited the example of chipmaker Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., which was granted $6.6 billion in CHIPS funding, deciding to increase its U.S. investments. The company unveiled plans in March to invest $100 billion in U.S. manufacturing, on top of a previously announced $65 billion. “So if the question is, ‘Are we renegotiating?’ The answer is, ‘Absolutely, for the benefit of the American taxpayer,’” Lutnick said

The secretary made the comments as senators grilled him over his department’s proposal to cut 16.5% of its budget, including a $325 million cut to the National Institute of Standards and Technology, which oversees CHIPS and Science Act funding programs. Lutnick was on Capital Hill Wednesday to defend the department’s proposal, part of the federal funding bill currently making its way through Congress.

In its budget proposal, department officials said the cut to NIST was due to its “development of curricula that advance a radical climate agenda.” While the proposal does not mention the CHIPS program, its staff and future have both been called into question by the White House. The Trump administration has fired dozens of NIST employees that worked on CHIPS initiatives, according to a NextGov report. The president has also publicly called for an end to the law and its funding.

“Your CHIPS Act is a horrible, horrible thing. We give hundreds of billions of dollars, and it doesn’t mean a thing. They take our money, and they don’t spend it,” Trump said in ajoint address to Congress March 4. Democratic Sen. Jeff Merkley of Oregon told Lutnick during the hearing that he worries renegotiating previously finalized contracts could slow down project timelines and unsettle chipmakers that now find the status of their funding in jeopardy.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://www.manufacturingdive.com/news/lutnick-chips-act-renegotiating-contracts-trump-budget-bill/749857/

4. CRITICAL METALS

“Nth Cycle is Bringing Critical Metals Refining to the US,” Zach Winn, MIT News, June 27, 2025

Much like Middle Eastern oil production in the 1970s, China today dominates the global refinement of critical metals that serve as the foundation of the United States economy. In the 1970s, America’s oil dependence led to shortages that slowed growth and brought huge spikes in prices. But in recent decades, U.S. fracking technology created a new way to extract oil, transforming the nation from one of the world’s largest oil importers to one of the largest exporters.

Today the U.S. needs another technological breakthrough to secure domestic supplies of metals like lithium, cobalt, copper, and rare earth elements, which are needed for everything from batteries to jet engines and electric motors. Nth Cycle thinks it has a solution. The company was co-founded by MIT Associate Professor Desirée Plata, CEO Megan O’Connor, and Chief Scientist Chad Vecitis to recover critical metals from industrial waste and ores using a patented, highly efficient technology known as electro-extraction.

“America is an incredibly resource-rich nation — it’s just a matter of extracting and converting those resources for use. That’s the role of refining,” says O’Connor, who worked on electro-extraction as a PhD student with Plata, back when both were at Duke University. “By filling that gap in the supply chain, we can make the United States the largest producer of critical metals in the world.”

Since last year, Nth Cycle has been producing cobalt and nickel using its first commercial system in Fairfield, Ohio. The company’s modular refining systems, which are powered by electricity instead of fossil fuels, can be deployed in a fraction of the time of traditional metal refining plants. Now, Nth Cycle aims to deploy its modular systems around the U.S. and Europe to establish new supply chains for the materials that power our economy.

“About 85 percent of the world’s critical minerals are refined in China, so it’s an economic and national security issue for us,” O’Connor says. “Even if we mine the materials here — we do have one operational nickel mine in Michigan — we then ship it overseas to be refined. Those materials are required components of multiple industries. Everything from our phones to our cars to our defense systems depend on them. I like to say critical minerals are the new oil.”

From waste, an opportunity:

In 2014, O’Connor and Plata attended a talk by Vecitis, then a professor at Harvard University, in which he discussed his work using electrochemical filters to destroy contaminants in pharmaceutical wastewater. As part of the research, he noticed the material was reacting with metal to create crystalline copper in the filters. Following the talk, Plata asked Vecitis if he’d ever thought about using the approach for metal separation. He hadn’t but was excited to try.

At the time, Plata and O’Connor were studying mineral-dense wastewater created as a byproduct of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas.“The original thought was: Could we use this technology to extract those metals?” O’Connor recalls.

The focus shifted to using the technology to recover metals from electronics waste, including sources like old phones, electric vehicles, and smartwatches. Today, manufacturers and electronic waste facilities grind up end-of-life materials and send it to huge chemical refineries overseas, which heat up the metal into a molten liquid and put it through a series of acids and bases to distill the waste back into a pure form of the desired metal. “Each of those acids and bases have to be transported as hazardous goods, and the process for making them has a large greenhouse gas and energy footprint,” Plata explains. “That makes the economics difficult to square in anything but huge, centralized facilities — and even then it’s a challenge.”

The United States and Europe have an abundance of end-of-life scrap material, but it’s dispersed, and environmental regulations have left the West few scalable refining options.

Instead of building a refinery, Nth Cycle’s team has built a modular refining system — dubbed “The Oyster” — which can reduce costs, waste, and time-to-market by being co-located onsite with recyclers, miners, and manufacturers. The Oyster uses electricity, chemical precipitation, and filtration to create the same metal refining chemicals as traditional methods. Today, the system can process more than 3,000 metric tons of scrap per year and be customized to produce different metals. “Electro-extraction is one of the cleanest ways to recover metal,” Plata says.

Nth Cycle received early support from the U.S. Department of Energy.

Onshoring metal refining:

Plata says one of the proudest moments of her career came last year at the groundbreaking ceremony for Nth Cycle’s first mixed hydroxide (nickel and cobalt) production facility in Ohio. Many of Nth Cycle’s new employees at the facility had previously worked at auto and chemical facilities in the town but are now working for what Nth Cycle calls the first commercial nickel refining facility for scrap in the country.“O’Connor’s vision of elevating people while elevating the economy is an inspiring standard of practice,” Plata says.

Nth Cycle will own and operate other Oyster systems in a business model O’Connor describes as refining as a service, where customers own the final product. The company is looking to partner with scrap yards and industrial scrap collection facilities as well as manufacturers that generate waste. Nth Cycle is mostly working to recover metals from batteries today, but it has also used its process to recover cobalt and nickel from spent catalyst material in the oil and gas industry. Moving forward, Nth Cycle hopes to apply its process to the biggest waste sources of them all: mining. “The world needs more critical minerals like cobalt, nickel, lithium, and copper,” O’Connor says. “The only two places you can get those materials are from recycling and mining, and both of those sources need to be chemically refined. That’s where Nth Cycle comes in. A lot of people have a negative perception of mining, but if you have a technology that can reduce waste and reduce emissions, that’s how you get more mining in regions like the U.S. That’s the impact we want.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://news.mit.edu/2025/nth-cycle-brings-critical-metals-refining-0627

5. CHINA’S CHOKE POINTS

“The Vulnerabilities Holding Back Chinese Industry,” Edward White and Harry Dempsey, Financial Times, June 30, 2025

China has risen to be a global powerhouse, the world’s second-biggest economy and one of two true military superpowers. And yet, as the country’s leaders in Beijing are acutely aware, the nation has not been able to overcome dozens of industrial “choke points”. From a Western standpoint, the good news is that these choke points are ultimately holding back China’s quest for independence and leave it vulnerable to US pressure in an era of trade wars and export controls. As well as cutting-edge computer chips, they also include a series of obscure components and materials that are essential building blocks of modern manufacturing.

The bad news, for the west and its companies at least, is that China is addressing these problems in a methodical and systematic manner and is using tools such as AI to advance more quickly. Leading European, Japanese and American rivals, which have long been insulated from competition from China because of problems with quality and inconsistent yield in Chinese factories, are now on high alert. “What should give us pause is that the dynamic of China’s technological dependency on the west is rapidly changing,” says Elisa Hörhager, the Beijing-based chief representative in China of the Federation of German Industries, known as BDI.

“Many foreign companies still hold a clear edge when it comes to high-quality industrial products, thanks to their reputation for precision and engineering excellence. But Chinese competitors are catching up fast.” While several choke points, such as advanced semiconductor manufacturing, remain years, if not decades, from being conquered, others appear close to being resolved. These products include carbon fiber used for aviation and ball bearings. In the bearings sector, for example, China is the biggest bearings market but makes only 25% of the world’s supply.

Successive American presidents have steadily expanded export controls to restrict access to cutting-edge technologies, fearful that China’s technological might benefits the country’s military and threatens US national security. These controls — or the threat thereof — have driven Beijing to throw more resources into mitigating its vulnerabilities than they would have otherwise, says Kyle Chan, a researcher in Chinese industrial policy at Princeton University.

The motivation for Xi’s quest for industrial self-sufficiency has only intensified since Donald Trump returned to the White House and launched a global trade war that threatens to accelerate the decoupling of the world’s two biggest economies.

In lithium battery separators, China still imports about a $0.5 billion a year but now exports over $2 billion a year. In machines for making semiconductors including lithography machines, China imports close to $50 billion a year while it exports only some $0.5 billion. In electron microscopes, China now exports $2 billion a year and imports almost none. Georgetown’s CSET program has identified 14 industrial chokepoints that China still faces.

Among those choke points identified in 2018 that have since been resolved are high-end radio frequency components and operating systems — technologies where Huawei has become self-sufficient — as well as lithium battery separators, where Chinese suppliers like CATL and BYD are now world leading, and lidars, the laser sensors used in self-driving cars, which are also dominated by Chinese suppliers.

One area where Chinese firms continue to use outside suppliers is carbon fiber composite cascades, which are used in an engine’s casing to help aircraft land safely. Japanese group Nikkiso has a market share of 90 per cent. Takeshi Iwaoka, head of the aerospace division at Nikkiso, dismisses the threat from China, saying that rival companies have been trying for 40 years to catch up without success.

Following the breakout success of DeepSeek — the AI developer that rocked the tech world with advances achieved with far less computing power than US rivals — there is, domestically at least, a renewed sense of confidence in China’s homegrown technological capabilities, even in the context of being cut off from US technology. In February, Ren Zhengfei, founder of tech group Huawei, was among a select group of business leaders to meet Xi in Beijing. Seated opposite the Chinese leader, Ren told Xi that Huawei is spearheading a coalition of more than 2,000 companies aiming to boost Chinese semiconductor supply chain self-sufficiency to 70 per cent by 2028.

Angela Huyue Zhang, a professor of law at the University of Southern California and a leading expert on China’s technology regulation and policy, cautions against viewing China’s choke point progress as a quest to be “number one” in a race against the US. “Washington has misunderstood China’s goals; the real goal for China is to increase self-sufficiency, improve productivity, and drive economic growth — outcomes that will ultimately enhance the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist party,” she says. “Tech development is only a means to achieve these goals; it is not an end in itself.”

Excerpted with edits; more at (paywall): https://www.ft.com/content/292e44c6-f924-4fd5-b574-484f3c67d551

6. EAT DUST?

“How China’s New Auto Giants Left GM, VW and Tesla in the Dust, ” Nick Carey and Norihiko Shirouzu, Reuters, July 3, 2025

China’s emerging automotive dominance owes largely to a singular manufacturing achievement – slashing vehicle-development time by more than half, to as little as 18 months for an all-new or redesigned model. The average age of a Chinese-brand electric or plug-in hybrid model on sale domestically is 1.6 years, versus 5.4 years for foreign brands, consultancy AlixPartners found.

That speed has rattled legacy automakers, which have historically redesigned vehicles about once every five years, or once a decade for pickups. This account of how Chinese automakers outmaneuvered global rivals is based on interviews with more than 40 people, including current and former executives, employees and investors at five Chinese and seven global automakers and more than a dozen industry experts. Reuters visited BYD’s Shenzhen headquarters, factories of Chinese EV brands Zeekr and Nio, and European R&D centers of Zeekr and Chery.

The U.S. and Europe have imposed tariffs to shield their car industries, alleging China unfairly subsidizes EVs. But Chinese automakers’ development speed has emerged as the biggest factor in their cost and technological advantages over foreign competitors, Reuters found. Shaving years off vehicle-development cycles saves capital, lowers prices and ensures Chinese players have the freshest models during a technological revolution, executives and industry experts said.

The urgent pace is baked into BYD’s structure. Taking advantage of China’s lower labor costs, BYD deploys about 900,000 employees, nearly as many as the combined workforces of Toyota and Volkswagen, to accelerate design and manufacturing. At its headquarters, BYD promotes a work-focused life through company-subsidized housing, transportation and schools. Unlike most automakers, BYD makes most of its own parts rather than relying on suppliers, another factor that speeds development and lowers costs.

Chinese automakers’ employees often work six 12-hour days a week, said Peter Matkin, Chery’s chief international-brands engineer. “Global automakers have no idea what they’re up against,” he said. BYD and Chery each increased sales by about 40% globally in 2024, as U.S. EV pioneer Tesla saw its first annual sales decline, due largely to its aging model lineup. This year, Tesla’s sales are falling as CEO Elon Musk alienates many customers with his right-wing political activities.

Chinese automakers’ gains have come at the expense of global rivals. From 2020 to 2024, the top five foreign automakers in China — Volkswagen, Toyota, Honda, General Motors and Nissan — collectively saw their passenger-car sales in that market plunge from 9.4 million annually to 6.4 million, according to data provided to Reuters by consultancy Automobility. Today’s top five Chinese automakers saw sales more than double to 9.5 million last year from 4.6 million vehicles in 2020. China’s leading foreign automaker, Volkswagen, now develops vehicles with China’s Xpeng, a fast-growing EV maker. Other global automakers, including Toyota and Stellantis, have pursued similar partnerships with Chinese counterparts to learn how they operate.

Chinese automakers release good-enough vehicles quickly, with less emphasis on quality and with far fewer prototypes and a fail-fast philosophy mirroring Silicon Valley tech startups, industry executives and experts said. They lean more on simulations and artificial intelligence than real-world testing for safety and durability. They treat model launches more like the start than the end of development, adding frequent upgrades based on consumer feedback.

This urgency stems in part from fierce competition that’s creating more losers than winners: 93 of 169 automakers operating in China have market shares below 0.1%, according to research firm JATO Dynamics. Few make a profit, a struggle exacerbated by overcapacity. China's assembly lines can produce 54 million cars annually, almost double the 27.5 million the factories produced last year, according to consultancy Gasgoo Research Institute. With supply exceeding demand, automakers are slashing prices.

China’s EV-price war sparked alarm after BYD in May discounted 20 models, including its entry-level Seagull, which was selling for 55,800 yuan ($7,789). Great Wall Motor Chairman Wei Jianjun called the industry “unhealthy,” citing an increasingly common industry practice of dumping surplus new-vehicle inventory by selling zero mileage cars as “used” at steep discounts in China.

To offset losses, China automakers are racing to boost exports globally. In many countries, their vehicles fetch prices on par with comparable models from global automakers – and aboutdouble the retail prices, opens new tabthe Chinese-brand cars sell for at home.

Excerpted with edits; more at:https://www.reuters.com/investigations/how-chinas-new-auto-giants-left-gm-vw-tesla-dust-2025-07-03/

7. HISTORICALLY WAGES ARE UP

“American Wages Really Have Gone Up,” Noah Smith, Noahopinion, July 7, 2025

For years, we’ve been deluged with charts and rhetoric and memes about how American wages haven’t gone up for decades. No. The basis for this claim is one particular data set: average hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers in the private sector, divided by the consumer price index. That measure of wages was indeed lower in 2019 than in 1973. But if you use the PCE price index instead — which measures the changes in the prices of what people actually consume, rather than what they used to consume in the past — you see a very different story:

This is enough to show that the U.S. economy as a whole is delivering wage growth (though less than we’d like, of course). But what we really care about on a personal level, when it comes to wage trends, is probably some combination of two questions:

How much do a typical person’s wages increase over time?

Do young people make more than their parents did at a similar age?

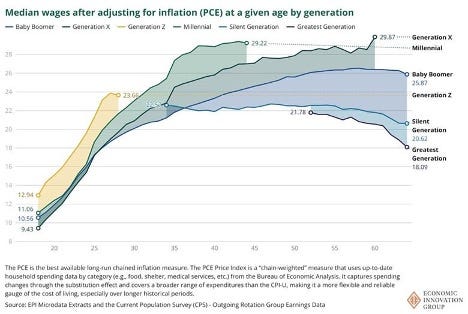

The Economic Innovation Group has a chart that allows us to see the answer to those two questions in a nutshell:

We can see that every American generation’s income, except for the Silent Generation, has risen strongly over the first two decades of their working life. We can also see that Gen Xers started earning more than the Boomers after about age 27, and that Millennials started earning more than the Xers around age 25. Those generation gaps widened over time, as the younger generations pulled away from the older ones.

Most importantly, we can see that Zoomers — the current young generation — beat the wages of the Millennials, Xers, or Boomers right out of the gate. Gen Z has benefitted from a strong re-acceleration of American wage growth since the early 2010s.

Excerpted with edits; more at: https://www.noahpinion.blog/p/at-least-five-interesting-things-4c7

The MIT Initiative for New Manufacturing (INM) aims to redefine what’s possible in manufacturing. Through research, hands-on training, and deep industry collaboration, INM aims to build the tools, systems, and talent to shape a more productive, sustainable, and resilient future. INM is a campus-wide manufacturing effort directed by Professors Suzanne Berger, A. John Hart and Christopher Love that convenes industry, government, and non-profit stakeholders with the MIT community to accelerate the transformation of manufacturing..

MIT’s Bill Bonvillian and David Adler edit this Update. We encourage readers to send articles that you think will be of interest to us at mfg-at-mit@mit.edu.

Subscribe to the MIT Initiative for New Manufacturing Substack

Insights from articles and reports of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad