Manufacturing Update - 10 December 2025

Insights from articles and reports, excerpted and summarized, of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad.

Content:

US DEVELOPMENTS:

1. WHAT ABOUT IMPLEMENTING AI? “America Is Winning the Wrong AI Race”

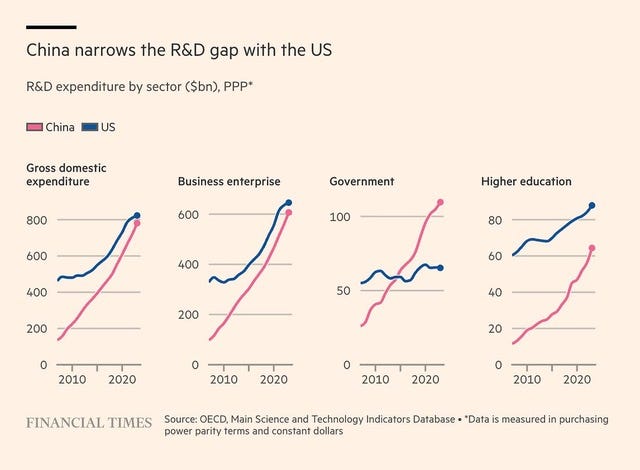

2. US LEADERSHIP OF R&D NARROWING: “China Narrows the R&D Gap with the US”

3. WHAT ARE THE TARIFF RESPONSES FOR COMPANIES? “How Painful Will Trump’s Tariffs Be for American Business?”

4. $10 MILLION SBA LOANS FOR MANUFACTURERS: “House Lawmakers Pass Bill to Double SBA Loan Limits for Manufacturers”

RARE EARTHS:

5. RARE EARTH ALTERNATIVES: “An Auto Holy Grail: Motors that Don’t Rely on Chinese Rare Earths”

6. CHINA GETS CONTROL OF MAJOR AUSTRALIAN-OWNED NEW RARE EARTH SOURCE: “The Failed Crusade to Keep A Rare Earths Mine Out of China’s Hands”

CHINA DEVELOPMENTS:

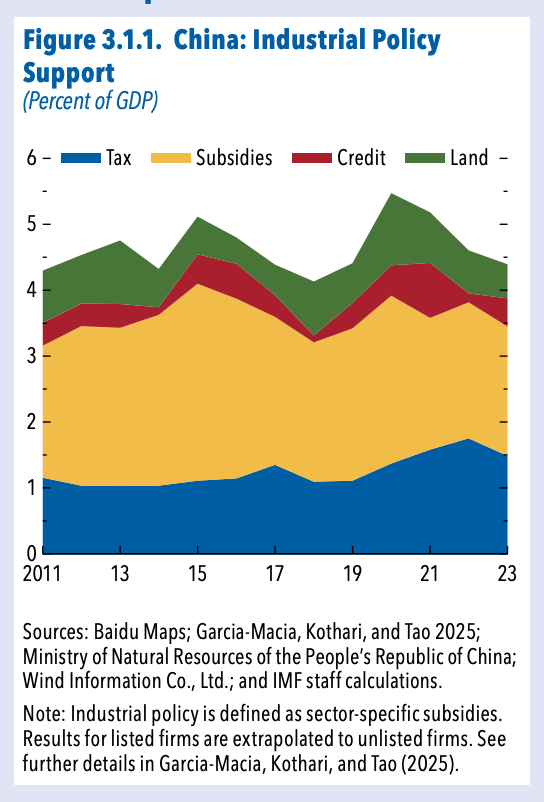

7. CHINA’S INDUSTRY SUBSIDIES BETWEEN 4 AND 5% OF GDP: “Chart: China: Industrial Policy Support”

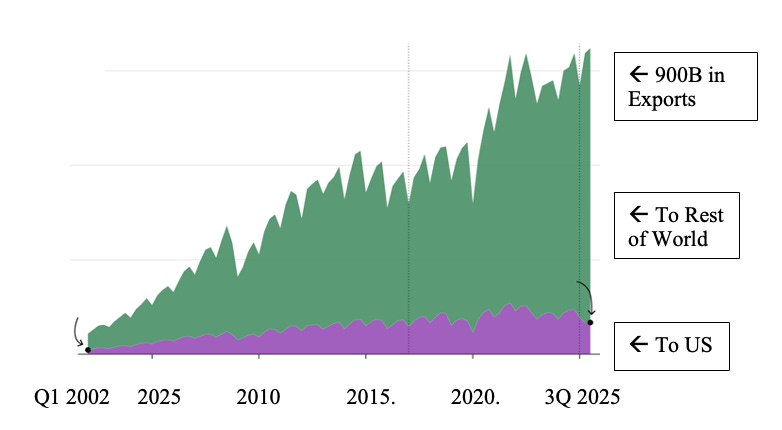

CHINA’S WORLDWIDE MANUFACTURING EXPORTS KEEP GROWING:“What Trade War? China’s Export Juggernaut Marches On”

US Developments:

1. WHAT ABOUT IMPLEMENTING AI?

“America Is Winning the Wrong AI Race,” Mehdi Alhassani and Anthony Bak, Wall Street Journal (opinion), May 16, 2025

The U.S. is winning an AI race—but it’s the wrong one. American policymakers have assumed that artificial general intelligence, or AGI, is achievable relatively soon, and so the aim has been to maintain an 18-month lead over China in reaching it. Washington has restricted Beijing’s access to advanced chips, built AI energy infrastructure, and imposed export controls on other components. This has kept the U.S. ahead in the sprint for AGI, but it’s a contest that can’t be won. America should turn to a different, winnable AI race.

Experts shift the goal post for AGI, or “true intelligence” such as you’d see in a person, with each AI advance. Mastering chess and writing a coherent essay were once held out as AGI benchmarks. AI can now do both, but clear, obvious gaps with human capabilities persist. AGI is a philosophical goal—a perpetually receding horizon—rather than a practical target for strategic victory.

But even if experts could arrive at a stable definition for AI technological supremacy, trying to be the first nation to hit that goal isn’t a smart policy priority. Because of how AI advances, foreign competitors will quickly catch up and likely using far fewer resources.

Model capabilities increase logarithmically with the hardware resources used to train them. In effect, this means you can make a model 90% as good as the model on the current frontier of AI performance with only 10% of the hardware. This is why limiting access to graphics processing units won’t stop America’s competition. Foreign companies and governments, even those with a fraction of the resources, will still be able to push neck-and-neck with U.S. companies. It was inevitable that a Chinese model like DeepSeek—open-source, cheaply trained—would come along to challenge American pre-eminence in AI, regardless of how tightly Washington controlled chip exports.

Moreover, key AI hardware and software are rapidly becoming more efficient. Something like Moore’s Law—the observation that CPUs double in capacity about every two years—has proved roughly true for GPUs, too. At the same time, algorithmic improvements are driving model efficiency hard enough that smaller models can quickly catch up to those on the cutting edge of AI capability. The sort of advanced AI that today requires historic data-center investments will become accessible to more global players with moderate infrastructure tomorrow.

While America can’t stop global AI model competition, what we can do is lead the race for AI implementation. What will determine if a nation is ahead on AI isn’t if it has the best models first, but if it is translating AI into widespread benefits for society. This means bringing the best models into organizations’ core missions and processes, from the factory floor to the operating room to the battlefield.

Consider healthcare. Hospitals collect reams of data. The ability of a nurse or doctor to synthesize critical factors in a patient’s case rapidly can be the difference between his getting better and worse, or even life and death. Leading hospitals have started using AI-driven systems to capture bed capacity, diagnoses, staffing patterns, surgical operations and more. Decisions that would have taken hours or even days can be made in seconds.

In manufacturing, AI can encourage progress toward what may seem like opposing goals—efficiency and resiliency. On the factory floor, AI models can detect defects, letting companies catch faulty parts before they ship. AI can also more quickly identify the root causes of mistakes and prevent future faults. Outside factory walls, AI can capture every link in a supply chain, monitoring real-time disruptions and allocating resources accordingly. On the battlefield, AI can make militaries faster and more lethal than ever before.

This is the sort of AI competition that matters. There isn’t one goal but many spread across the economic and policy worlds. To make progress, the U.S. must focus on carefully smoothing the path for AI integration in each sector and rapidly invest in unleashing the technology’s transformative power to improve lives and solve real-world problems. That’s what winning the AI race looks like.

Excerpted with edits: https://www.wsj.com/opinion/america-is-winning-the-wrong-ai-race-technology-war-34ee352e

2. US LEADERSHIP OF R&D NARROWING

“China Narrows the R&D Gap with the US,” Financial Times (based on OECD data), November 30, 2025

Excerpted with edits (paywall): https://www.ft.com/content/3eccd40e-5ec0-43e8-a521-3b87e29e323b

3. WHAT ARE THE TARIFF RESPONSES FOR COMPANIES?

“How Painful Will Trump’s Tariffs be for American Business? Wall Street Journal, December 3, 2024

Companies can respond to tariffs in three ways. The first is to stockpile goods. Microsoft, Dell and hp are among the American tech companies that are rushing to import as many electronic components as possible before the new administration takes office in January. Yet there are limits to that strategy. Stockpiles may be depleted well before tariffs are lifted. And holding inventory requires warehouses and ties up cash. Many big companies already expanded their inventories in the wake of the supply-chain mayhem of the pandemic, and may have limited appetite to increase them further, particularly as higher interest rates raise the cost of doing so. According to JPMorgan Chase, another bank, the average ratio of working capital to sales among America’s 1,500 most valuable listed companies last year was higher than at any point in the past decade except 2020.

The second option for companies is to pass tariffs on to customers by raising prices. Several firms, including Stanley Black & Decker and Walmart, America’s biggest retailer by sales, have already indicated that they may do so. Again, however, there are limits. The excess savings Americans built up during the pandemic have been whittled away by inflation and there are signs the country’s jobs market is cooling. The delinquency rate on credit cards is at its highest in a decade.

The third, and most difficult, response is to rewire supply chains. New suppliers, once found, have to be tested and negotiated with, a process that can take years. Many American companies have already begun diversifying their supply chains away from China. According to Kearney, a consultancy, China’s share of America’s manufactured-goods imports fell from 24% in 2018 to 15% last year. Meanwhile, the share from other low-cost Asian countries and Mexico, respectively, rose from 13% to 18% and from 14% to 16% (see chart 1). An analysis by Fernando Leibovici and Jason Dunn of the Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis shows that the fall in China’s share of imports has been biggest in industries where America has been most dependent on its rival, including communications and information technology.

Excerpted with edits (paywall): https://www.economist.com/business/2024/12/03/how-painful-will-trumps-tariffs-be-for-american-businesses

4. $10 MILLION SBA LOANS FOR MANUFACTURERS

“House Lawmakers Pass Bill to Double SBA Loan Limits for Manufacturers,” Manufacturing Dive, Nathan Owens, December 3, 2025,

The U.S. House of Representatives on Monday unanimously passed a bill that would double the Small Business Administration’s loan limit from $5 million to $10 million for domestic manufacturers. The Made in America Manufacturing Finance Act aims to unlock more capital for small manufacturers seeking to buy machinery, expand their factories, upgrade equipment or scale production. The bill has advanced to the Senate for further consideration.

The bill, introduced by Rep. Roger Williams, of Texas, aligns with the SBA’s Made in America Manufacturing Initiative, an effort to rebuild the nation’s industrial leadership by cutting regulations and expanding access to capital for small manufacturers. The legislation would offer increased limit guarantees for 7(a) and 504 loans to small manufacturers with production facilities entirely located in the United States. In other words, companies relying even a small amount on international production for their supply chain wouldn’t qualify for the increased limits

Excerpted with edits: https://www.manufacturingdive.com/news/house-pass-sba-loan-bill-made-in-america-finance-act-10-million/806904/

See also: https://www.congress.gov/119/bills/hr3174/BILLS-119hr3174rh.pdf

RARE EARTHS:

5. RARE EARTH ALTERNATIVES

“An Auto Holy Grail: Motors that Don’t Rely on Chinese Rare Earths,” Jack Ewing, New York Times, November 24, 2025

Stunned by frequent shortages of essential materials from China, automakers in the United States and Europe are quietly trying to reduce or eliminate the need for materials that have become entangled in superpower rivalries. The companies are exploring technologies and exotic materials that could replace magnets made with rare-earth metals that are used in dozens of parts in cars and trucks of all kinds. They include components like windshield wiper motors and the mechanisms that allow seats to be adjusted.

Magnets made with the rare-earth elements neodymium, dysprosium and terbium are especially important for the motors that move electric vehicles and hybrids, which are becoming more popular. China dominates mining and processing of most rare earths and has used its near monopoly as a diplomatic weapon. This year, it imposed controls on exports of some of those materials in apparent retaliation for President Trump’s stiff tariffs on Chinese goods.

The recent instability in rare-earth supplies is a much bigger threat to automakers than in the past. It has given new urgency to the search for motors that don’t need rare earths or for materials that would replace them. BMW’s electric vehicles already use motors that operate without rare earths. Researchers at Northeastern University and other institutions are working to synthesize materials that have promising magnetic properties and are found only in meteorites.

Start-ups have begun developing new kinds of motors and other technologies. And the Department of Energy is encouraging that work, despite the Trump administration’s rollback of other forms of support for electric vehicles. Many of these efforts won’t bear fruit for years. And substitute technologies like those used by BMW can be more expensive or have other drawbacks. For the time being, the industry remains extremely vulnerable to shortages that could bring assembly lines to a halt. This month, Beijing suspended some of its rare-earth export controls as part of an agreement with the Trump administration. But controls remain a threat as tensions between the United States and China continue.

Carmakers can use two strategies to keep their assembly lines running. They can find rare earths outside China, or they can switch to components that don’t require those metals.

General Motors is pursuing the first strategy with MP Materials, an American company that is mining rare earths in California. MP is also building a facility in Texas to refine the materials and use them to make magnets. Under an agreement announced in 2021, G.M. has promised to buy most of the output of the Texas factory for use in Cadillacs and Chevrolets. MP also has agreements with Apple and the Defense Department.

Such agreements provide companies like MP guaranteed revenue, something that wasn’t available to rare-earth companies and processors that went bankrupt after previous crises when prices fell so much that they couldn’t compete with Chinese suppliers. MP acquired its site in California from one such bankrupt company. But there is also a risk to automakers like G.M. They may wind up paying more than other manufacturers if shortages ease and prices fall again. G.M. is also searching for components that don’t need rare earths. “There’s nothing like not having to use rare-earth things, whether it’s magnets or batteries or whatever,” Mark Reuss, the president of G.M., said at a company event in New York recently. “How do we engineer out that dependency?”

BMW is using motors without neodymium or other rare earths in models like the iX sport utility vehicle. An electric current generates the magnetic field inside the motor that converts electrons to motion. A spike in the price of neodymium around 2011 prompted BMW to begin developing the technology. The luxury carmaker says it has largely solved the drawbacks of these motors, which tend to be heavier, bulkier and less energy efficient than those with rare earths. The company makes the motors in factories near its headquarters in Munich and in Austria. The motors are more efficient than those that use rare earths at the speeds required for everyday driving, said Stefan Ortmann, a BMW engineer. There are other advantages, he said. The magnetic field in BMW’s motors can be dialed up or down, and the motors are easier to keep cool. “We think it’s the sweet spot for us,” Mr. Ortmann said. A new version of the motor is even more efficient than earlier machines and will be installed in the iX3 S.U.V. that BMW will sell in the United States next summer. The company says that model will be able to travel 400 miles between charges.

Silicon Valley has also taken note of the rare-earth crisis. In rented garages in Sunnyvale, Calif., a start-up called Conifer has developed a compact, disc-shaped electric motor that can operate without rare earths. Rare-earth concerns have fueled interest in the technology, said Ankit Somani, a co-founder of Conifer. “Demand is not a problem,” he said. “Our main thing is how do we scale our production quickly.” But versions of the motors that use rare earths pack more power into a smaller package, Mr. Somani added.

\The auto industry’s holy grail would be material that matched the advantages of rare earths but did not come from China. Such materials exist, but only in small quantities around the globe. Tetrataenite, for example, is made of iron and nickel, which are abundant. But it takes hundreds of millions of years for the iron and nickel atoms to form the unique structure of tetrataenite, which occurs naturally only in meteorites. Laura Lewis, a chemical engineering professor at Northeastern University, and colleagues have developed a way to synthesize tetrataenite in weeks rather than eons. But there is still a long way to go before the material can be mass-produced, she said, and even then it will not replace rare earths in all applications.

Excerpted with edits: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/24/business/automakers-rare-earth-minerals-magnets.html

6. CHINA GETS CONTROL OF MAJOR AUSTRALIAN-OWNED NEW RARE EARTH SOURCE

“The Failed Crusade to Keep A Rare Earths Mine Out of China’s Hands,” Wall Street Journal, November 22, 2025

For years, a mining project in Africa held the promise of helping free the West from its dependence on China for rare earths. Some weeks back, it fell into Chinese hands. The failure of Peak Rare Earths, an Australian mining company, to build a China-free supply of rare-earth minerals offers a look at how Beijing came to dominate the global supply of critical minerals—a position it is now deftly leveraging for geopolitical gain. China has choked off the supply of rare earths to wring key concessions from President Trump in his trade war.

Promising New Mining Source Goes to China: The sale of Peak to a Chinese rare-earth behemoth earlier this autumn is part of a pattern that means that, by 2029, Beijing will receive all the rare earths flowing from Tanzania, one of the world’s major emerging sources of the elements, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. Some liken it to the grip China enjoys today over cobalt production in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“This is a very strategic loss,” said Gracelin Baskaran, a critical-minerals expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “This increases [Chinese] market power and it increases their market capacity to destabilize an already very fragile market.”

By 2019, Rocky Smith, then CEO of Peak, asked foreign governments for help in developing the Tanzania mine. His timing was good. Trump was in the midst of a trade war against Beijing, and Chinese state media warned China could use rare earths as a weapon. “The United States risks losing the supply of materials that are vital to sustaining its technological strength,” a commentary in the People’s Daily said.

Smith secured a letter of interest from the Overseas Private Investment Corporation, a U.S. government institute that funded projects in the developing world. However, Tanzania’s then-leader John Magufuli opposed foreign mining projects, and the U.S. government backed off from funding. Other governments also declined to put money forward. In 2021, Magufuli died in office, and was succeeded by Samia Suluhu Hassan, who looked more favorably on foreign mining projects.

But Peak’s backers were growing antsy. In 2022 a cornerstone investor, U.K. private-equity firm Appian Capital Advisory, sold its 20% share in Peak to Shenghe Resources, a partly state-owned Chinese rare-earths juggernaut that has steadily bought up stakes in promising rare-earth deposits in Tanzania from Western companies that controlled them. Appian says that it had made repeated attempts to get U.K. government funding to push the project forward. “This would have provided a large part of the U.K. and Europe’s rare earths, but there was zero backing,” said Michael Scherb, Appian’s CEO. Peak’s management insisted that even with a large Chinese shareholder, it would stick to its plan to supply buyers outside of China.

Trump Tariff Effects: That commitment soon began to falter. In 2022 rare-earth prices started dropping as China jacked up production. That year, Peak made Bardin Davis, a banking veteran and Peak executive, its CEO, and appointed a new executive chairman. Shortly afterward, Peak announced an agreement with Shenghe whereby the Chinese company would receive between 75% to 100% of the mine’s output for seven years. Shenghe would also get a board seat.

Since Shenghe had bought its stake in the company, Western governments treated Peak as being part of the “nexus with China,” said Davis. That made it difficult to raise funds from Western funding agencies for its plans to develop the mine. Meanwhile, Peak risked losing its mining license in Tanzania if it didn’t make progress building the mine. The company embarked on a global search for joint-venture partners or buyers, but only received one indicative offer—from Shenghe. In 2024, Peak announced a plan to enter a joint-venture arrangement with Shenghe under which the Chinese company would invest to develop the mine.

But then, in response to stiff tariffs Trump slapped on China in April, Beijing implemented a new export control regime on rare earths that strangled global supply and sent shock waves through Western industry, which relies on the minerals to make everything from cars to drones and jet engines. Peak said it would formally scrap the planned joint venture with Shenghe, citing “recent geopolitical and regulatory developments.” A major problem, Davis said, were regulations Beijing had introduced in recent years restricting the export of Chinese rare-earth technology that would have made it difficult for the Australian and Chinese companies to work together.

The Long View: This May, Shenghe moved in, offering to buy all of Peak for a premium roughly eight times that of average mining and metals acquisitions, according to data from S&P Global Market Intelligence. The price, Shenghe said, was worth it for a mine it had long considered “the premier undeveloped rare earth project in the world.” In all, shareholders received roughly four times the pre-announcement share price from the Shenghe sale. In October, Peak was formally delisted from the Australian stock exchange. Shenghe now controls one of the world’s best rare-earth deposits.

The Chinese “have a long view on this stuff and the money part is not a big deal to them,” said Smith, who served as Peak’s CEO until 2020. Peak is “just one more piece, one more rare-earth deposit that they are going to be bringing into China.”

Excerpted with edits (Paywall): https://www.wsj.com/business/the-failed-crusade-to-keep-a-rare-earths-mine-out-of-chinas-hands-0774e66a

CHINA DEVELOPMENTS:

7. JUST WHAT ARE CHINA’S INDUSTRIAL POLICY SUBSIDIES?

“Industrial Policy in China: Quantification and Impact Misallocation,” Daniel Garcia-Macia, Siddharth Kothari, and Yifan Tao, IMF Report, August 2025

Industrial policies (IP), defined as policies aimed at changing the sectoral structure of the economy, have been widely used around the world, particularly in recent years. In China, IPs have long been a centerpiece of economic policy. The government has used an array of policy tools, including (but not limited to) cash subsidies, tax benefits, subsidized credit, subsidized land, trade and regulatory barriers, and industry coordination to promote certain economic sectors (State Council 2005). This has had a material impact on the economy, helping to develop specific industries and technologies, but also generating fiscal costs and potential

factor misallocation. However, official information on the size of IP support or the effects of such policies is for the most part unavailable. This paper aims to shed light on these two issues.

First, it quantifies the size of the main IP instruments in China using data from financial reports of listed firms and the land registry. Second, it estimates the impact of IP on domestic factor misallocation and aggregate productivity using a structural model. The combined findings are set forth in the chart below, showing, consistently over the years, IP subsidies ranging between 4.3 And 5.6 percent of China’s GDP. These levels dwarf those of any other nation.

Excerpted with edits: https://www.imf.org/-/media/files/publications/wp/2025/english/wpiea2025155-source-pdf.pdf

7. CHINA’S WORLDWIDE MANUFACTURING EXPORTS KEEP GROWING

“What Trade War?China’s Export Juggernaut Marches On,” Agnes Chang and Daisuke Wakabayashi, New York Times, November 3, 2025

China has offset the decline from America with breathtaking speed. Shipments to other parts of the world have surged this year, demonstrating that China’s manufacturing dominance will not be easily slowed. Chinese exports are on track to reach another record this year.That’s because China was prepared. It has been seeking out new customers for years, and its massive manufacturing investment allows it to sell goods at low prices. “They should not be surprised that China is able to find markets outside of the advanced economies,” said Mary Lovely, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Last week, Mr. Trump reduced the tariffs he imposed on China, though they remain at heights not seen in decades. He insists that his tariffs will force a revival of American factories and create jobs — a pledge that is contested by many economists and manufacturing experts. It is also unclear how effective hispolicies will be in stemming the flow of goods that originate in China and route through other countries before arriving in the United States.

China’s Global Exports Continue to Grow Despite Trump’s Efforts to Over $900 Billion:

The rest of the world is caught between the two superpowers. Some countries, including Vietnam (up 28%) and members of the European Union (up 11%), are deeply concerned about the risk posed by China’s exports to their own industries, and China faces a backlash in the form of tariffs in regions like Europe. Other nations, like Argentina (up 57%) and Nigeria (up 45%), are buying low-cost Chinese technology to modernize their economies but running up wider trade imbalances with China.

For years, Americans have turned to China to outfit their homes and stock their offices. While the volume of Chinese exports remains enormous, the declines this year are widespread and drastic. The United States is buying less of almost everything from China. But the shifts in China’s exports are part of what is expected to be a continuing and unpredictable transformation. Mr. Trump’s tariff reduction last week, which he said lowered overall tariffs on China to about 45 percent from about 55 percent, could stabilize China’s exports to the United States, said Gerard DiPippo, associate director of the RAND China Research Center.

Africa is another story. Many African countries bought few of these items from China before this year. China sold only about 100 electric cars to Nigeria two years ago; this year it has already sold thousands. Solar panel shipments to Algeria thus far this year are already nearly four times that of all of last year. China’s growing exports to Africa come as Mr. Trump has pulled back aid to the continent. Chinese companies are sacrificing profits by selling to Africa at low prices, but are, in many cases, gaining influence. “The margins may not be as high,” said Ilaria Mazzocco, a deputy director at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “But for those markets, it’s entirely transformational to have access to this technology at affordable prices.”

Excerpted with edits: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2025/11/03/world/asia/china-exports-trump-tariffs.html

The MIT Initiative for New Manufacturing (INM) aims to redefine what’s possible in manufacturing. Through research, hands-on training, and deep industry collaboration, INM aims to build the tools, systems, and talent to shape a more productive, sustainable, and resilient future. INM is a campus-wide manufacturing effort directed by Professors Suzanne Berger, A. John Hart and Christopher Love that convenes industry, government, and non-profit stakeholders with the MIT community to accelerate the transformation of manufacturing.

MIT’s Bill Bonvillian and David Adler edit this Update. We encourage readers to send articles that you think will be of interest to us at mfg-at-mit@mit.edu.

Subscribe to the MIT Initiative for New Manufacturing Substack

Insights from articles and reports of interest on manufacturing technology, management, policy, and economics in the US and abroad